A Thirty-Year Reflection on the Murder of Tommy Baer

Suddenly, we find we are no longer the actors, but the spectators of the play. Or rather we are both.

-Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

Thus I take leave of my lost city. Seen from the ferry boat in the early morning, it no longer whispers of fantastic success and eternal youth.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, “My Lost City”

History favors the eyewitness. In its quest for the truth of the past, it privileges the experiences of the firsthand participant. Life is complex, though, and sometimes it is the events we do not witness that overtake and overwhelm us. When those we love endure tragedy in our absence, the sense of having escaped it can bring remorse and guilt. “If only I had been there!” we tell ourselves, indulging the fantasy that we would have changed the course of events where others failed.

Such are my memories of thirty years ago this week. Though I know the principal event only from others’ accounts, I endured its aftermath, and it has shadowed my life and my friends’ lives for three decades. At the heart of even a familiar story, there is always something more to discover, and it is worthwhile, perhaps, to ponder it anew from time to time and, with T. S. Eliot, go back to where we started and “know the place for the first time.”

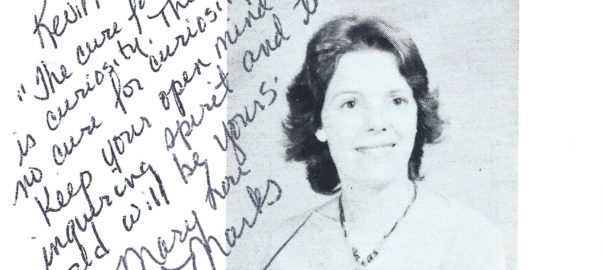

On June 1, 1988, I graduated from the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Neither my parents nor either of my brothers attended; I had no relatives there at all. This was a painful topic in my family for many years, but they are all gone now,1 and I can speak of it. It was sad and disappointing, but it could not be avoided, and they meant no harm. I probably would not have participated in the ceremony at all had not my girlfriend, Sheryl Moore,2 insisted that I do so and that she would be there for me, as she was. Sheryl attended the ceremony, for which she had even bought a new dress. I assume she took photos that day. I would give anything to have them now, but I don’t. She hugged me and later treated me to dinner. Memphis State University’s law school had accepted me for the fall term, and as graduation gifts Sheryl gave me a leather briefcase and a dark blue, beautifully bound copy of Black’s Law Dictionary.

Memphis was more than 300 miles from Knoxville, and I had arranged to spend the summer with my parents, in Benton County, before moving there. For the moment, though, I was more excited about my immediate plans. After graduation, I returned to my downstairs room in the Phi Kappa Tau house, at 1800 Lake Avenue, to pack. The next morning, Sheryl and I were driving to Charleston, South Carolina to spend a few days with her aunt and uncle, who lived near the beach on the Isle of Palms. I was 23 and had never been on a real vacation without my family, and I certainly had never taken a girlfriend on an out-of-town trip of this sort. It seemed such an adult thing to do. We had a wonderful time. Sheryl’s Uncle Bill, a pilot with his own small plane, flew us low over Fort Sumter, much to my delight. I was young. I was in love. I had many friends. I was now the first person in my family to earn a college degree. There was trouble back home, but I had big plans, and for the moment my future seemed bright.

On June 6, after dropping Sheryl off in Greenville, South Carolina, where her mother met us, I returned to the fraternity house, loaded my belongings into my bronze 1978 Oldsmobile Omega, and drove away from one of the only places where I was ever truly happy. Behind me I left a group of young friends, including some new initiates, soaking up the last days of spring in anticipation of a quiet summer and the fall semester pleasures to come: fraternity rush,3 parties, football, homecoming. The lawn was lush. The trees arrayed along the east side of the house stood like giant columns and looked as though they would be there forever. The ancient windows and doors were open, a breeze wafting through our 1920s Dutch Colonial Revival, which had been used hard by two decades of young men but had once been a mansion. It was, in Katherine Anne Porter’s words, “such a green day with no threats in it.”

Eleven weeks later, my friend Tommy Baer was murdered just a few feet from what had been my bedroom door.

The Delta Kappa Chapter of Phi Kappa Tau, of which I was, at the time of my graduation, the vice president for alumni affairs, initiated Thomas Holman Baer in the fall of 1987. Like several of our members, Tom had been active and successful in Scouting and had risen to Eagle Scout. Our chapter had strong ties to the Boy Scouts, and many of our best recruits came to us through those connections. Since Tom was younger than I was, and since I was not part of the Scouting world, I cannot claim to have known him very well, but I do have vivid memories of him. Most of all, I remember Tom’s positive, at times naïve outlook on the world; his gentle nature; his boundless energy; and his kindness. Tom was a caretaker, what some might call a “mother hen” type. At parties, he fretted and monitored, always on the lookout for problems or danger. He took pride in being a “first responder.” I wasn’t sure what that entailed, but he told me it meant he had been trained to handle a life-threatening emergency until help could arrive. It was clear that Tom had grown up with money, a boast I certainly could not make. The last real conversation I remember having with him was about his recent trip to New Zealand, which, though a popular vacation destination today, was exotic, to me anyway, in 1988. I marveled when Tom casually told me his airline ticket had cost $600. That was a small fortune to most undergraduates I knew, and I couldn’t comprehend someone younger than I was spending such a sum on leisure travel. Still, he exhibited no trace of self-importance. Tom was humble to a fault, and I never heard him say a bad word about anyone.

Early that August, I moved, alone, into the Highland Oaks Apartments on Walker Avenue in Memphis. There, I was soon miserable. The Highland Oaks was a poor choice for me. The door and the one large window in my apartment fronted a courtyard consisting of a rustic, forest-like green space dominated by two large oak trees that obviously long predated the building itself. I was on the ground floor, and everything was in deep shadow, even at midday. Little natural light entered my new home, and my mood, too, soon began to darken. From the outset, I found law school cynical and soulless. I missed Sheryl; I missed her so much I could hardly think of anything else—except the one big thing that had consumed me and all my family for nearly two years and had prevented them from attending my graduation. Back home, my brother Tim, 26, had recently been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, A.L.S. or Lou Gehrig’s disease. He was dying, and it wasn’t going to be merciful or quick.4 I was bereft, but I was also terrified. When I was among my friends in Knoxville, I had borne up well to the growing certainty of Tim’s diagnosis. Now, alone in my shadowy apartment and aware that some types of A.L.S. were genetic, I became obsessed with every muscle twitch, every cramp, every hint of weakness or fatigue. I found it difficult to concentrate, and I didn’t sleep well. Once, I even called Tim, who was still able to talk on the phone, and wept. Many years later, Greg, my other brother, would say of that period of Tim’s diagnosis and decline, “Every one of us should have been in counseling then.” A bright and exciting moment in my life had become harrowing and difficult. My closest friend and fraternity brother, Scott Walkup, was from Memphis and loved it above all other places. Now I was there, not loving it at all, and he was in Knoxville, where I most wanted to be. Everything seemed backward and strange and wrong, but I settled in as best I could and went to work on my courses, already sensing that none of this was going to work out.

Late on Saturday night August 20, my phone rang. It was Scott calling. We were close, Scott Walkup and I. We were as close as any two real brothers ever were. I knew him. He seemed breathless and sounded as though he were frightened or crying—or both. I knew instantly that something dreadful had happened and was immediately conscious of not knowing the details of Sheryl’s day, except that she was to have moved into her dormitory that afternoon. She and I had not been in touch since about Thursday, and a flood of dread welled up in me as I waited for Scott to explain his obvious distress. His words came like hammer blows, but they were not about Sheryl. Someone—an intruder—had come to the Phi Kappa Tau house and had stabbed Tom Baer on the marble walkway just a few feet from my old bedroom.

Seconds ago, I was sitting alone watching television, wrapped up in my own discontent and uncertainty. Now, I was reeling from this bizarre and unexpected crisis. I tried to impose order on Scott’s words. Though it was difficult to imagine the gentle Tom, of all people, in such a situation, hopeful images flashed through my mind: a scuffle, a hospital visit, stitches, some undesired attention from law enforcement, probably some unpleasantness with the U.T. Greek Life Office. Still, if these relatively benign images were accurate, why did Scott seem so frantic? I blurted questions to my friend and to myself. Stabbed? Tom? Why on earth would anyone attack Tom? At the Phi Tau house? That made no sense. School wasn’t even in session! Scott was there when it happened. He had, he said, held Tom’s head in his lap until help—the help Tom had always promised to summon for others—arrived. For now, as far as anyone knew for certain, Tom was still alive; Scott didn’t think so. He said he would call me back.

Sitting in a town that was not my home, in an apartment I already hated, I felt helpless and alone. Cut off from my panicked friends by 400 miles, seven hours, an unreliable car, and a lot of money I didn’t have, I had to muster my self-control to resist driving east at that very moment. I knew my fraternity brothers needed help, and I thought I might know where to find it, but I didn’t dare tie up the phone. I waited.

I didn’t have to wait long. After midnight, the phone rang again, sounding menacing somehow. I answered. Scott’s voice came in a flat monotone: “He died.” I replied in the way people do, telling myself I had misunderstood the words and, knowing I had not, quietly raging against their stark finality. “He died?” I asked, not wasting much emotion on the word. “Yep,” came my best friend’s bland reply. No one else was injured. A young man intruded on the house. Tom intervened. The intruder stabbed him in the chest. Tom fell outside the veranda door and never said another word after that. We talked for a minute or two and hung up. Scott was in good hands, I knew, accompanied by Ann Langdon, his sensible and reliable girlfriend, and I realized he probably needed time to speak to his parents, who lived in Memphis, just across town from me.

I had a sensible and reliable girlfriend too, and I wanted to talk with her above all else, but, even at this distance, I had reverted to fraternity officer mode. I had to prioritize. I did not have time to grieve—not yet. There was a murder in what had been my home. A friend and brother was dead. Our officers, including Scott, were all capable young men, but, like me, they were young men. Emotional and legal nightmares loomed at the very moment the new semester was to begin. Chaos, I thought, surely prevails at 1800 Lake Avenue tonight. I asked myself what I would do if I were there in Knoxville. There was only one answer, really, and it had been germinating in my mind since the first phone call: I would contact our most dependable alumnus, Gene Perkins, who had sheltered and advised our fraternity for years. Gene would know what to do; Gene would help. I called his number, waking him. There was no small talk. I began by explaining that I was in Memphis, not Knoxville. Scott, I continued, had informed me that someone had “come to the fraternity house and murdered Tom Baer.” Gene was shocked, of course, but he was good in a crisis. Though it was late at night, he said he would go to the house right away. I knew that was what he would do.

Confident that a trusted adult was taking the reins in Knoxville, I turned my attention to my own loss. Writing today, it seems so strange to recall the difficulty of maintaining contact with loved ones just a few decades ago. Sheryl’s friends were my friends, and I knew I had to call her, but, strangely, I didn’t know how to do it. I couldn’t remember which dorm she had moved into and wasn’t entirely certain she had done so yet. Hesitating in that late hour, and knowing it was an hour later still in Kingsport, Tennessee, her hometown, I reluctantly called her mother’s house. Sheryl’s mom was understandably alarmed when she realized who I was, and at first our conversation was a tangled mess, as I tried to assure her that her youngest child was fine, as far as I knew, and that I was not even in Knoxville. Finally, I was able to explain the bare outline of what had happened and that I needed only to speak to her daughter. Gracious and sympathetic, considering the hour and the startling nature of my call, Mrs. Moore gave me Sheryl’s dorm number, which she had written down just hours earlier.

I called the number. Sheryl and I had met at a Phi Kappa Tau rush party a year earlier. I happened to be standing inside the front door when she walked in with some friends. I thought her face strikingly beautiful and, brimming with home-team confidence I possessed in no other setting, I told her so. I said she reminded me of someone from another era—someone from the golden age of film, or from classic TV, maybe. I thought for a moment, and it came to me. I told her she resembled an ’80s version of the actress (Sue Randall, though I did not know her name then) who played “Miss Landers,” Beaver’s lovely teacher on Leave it to Beaver. I was sincere in this, and she laughed, but nothing came of it. She was in and out of the house from time to time that fall and winter, and at the end of the following March, right after my 23rd birthday, we became a couple.

Since our first meeting, Sheryl had made many friends at the fraternity house, so by August 1988 she knew Tom about as well as I did. Tonight, she was in Clement Hall, only about three blocks from the scene of his murder, and in that day before campus alert texts and “shelter in place” advisories, the news stunned her. We talked into the night, and it was only then, as we discussed what had happened and the dreadful fallout that was sure to follow, that I began to cry. The sunny days of early June seemed far away now, but I was no longer alone, and for that I was grateful. We discussed my driving to Knoxville. I wanted to go, and she wanted me to as well, but we both knew I couldn’t. My courses were demanding beyond anything I had known, and the attendance policy in Contracts, which would meet on Monday morning, was draconian. Legal Methods would meet for three hours on Monday evening. I wasn’t going anywhere.

Around five o’clock, I lay down on the bed, worried about Scott, Ann, and my other friends and hoping someone was looking after them all. I was lonely again now, for without Scott I knew almost no one in Memphis. I wanted to call home but hesitated. My brother’s terminal illness, conclusively diagnosed the previous January, was a crushing blow to our parents. They were rural, working-class people with limited resources. Well into their forties, they were now adjusting to a multitude of new and unexpected burdens, and I hated to wake either them or Greg, my younger brother, on a Sunday morning. I considered calling or even visiting the Walkups, Scott’s parents, but I thought better of that too. Scott had already spoken with them, and I had alarmed enough people for one night. Thinking the murder of a student on the flagship campus of the state’s premier university system would be big news, I turned on the radio and tried to listen and sleep at the same time, enduring hours of pop music so I could hear the Tennessee Radio Network News at the beginning of each. No one mentioned the murder. Finally, at about eight o’clock, I called my mother. Mom didn’t know Tommy and had never been to the fraternity house, but we were close, and I needed to share what had happened and to get her loving, practical take on things. After that, I slept much of the day.

On Sunday evening, I spoke with Sheryl, Scott, Stacy Prowell (a close friend and my former roommate at the fraternity house), and others. A coherent story was emerging. There had been perhaps two dozen people at the house. Big social events were planned for rush in the coming days, but rush parties sometimes swelled to a hundred people or more. Typically, around twelve members of the fraternity resided in the house, and the August 20 gathering, which the police and the media would later describe as a “party,” was little more than a few brothers and friends stopping by to visit with those who lived there. There was beer in the house, it seems, in violation of university policy, but I had rarely known there to not be beer somewhere in the house or in any house on the row. Move-in day celebrants and others wandered up and down the strip, a block away, going in and out of the restaurants and pubs there and along the neighboring streets. Among the latter was Gatti’s, formerly Mr. Gatti’s Pizza, directly across Lake Avenue from the fraternity house. Gatti’s was a popular watering hole for the Phi Taus and all of “Old Row,” as distinguished from “New Row,” the “rich” fraternities along the river, on the other side of the campus.

As the Phi Kappa Taus and their friends chatted and exchanged summer stories, Jeffrey R. Underwood, a twenty-year-old local man who was not a student, left Gatti’s sometime around eleven o’clock, crossed the street with three friends, and entered the house. Underwood was rude and pushy, claiming he had been invited and asking to see someone named John. There was no one by that name at the house, and when a member told them to leave the four did so. Over the next hour, Underwood reappeared and was asked to leave at least twice more. When he began harassing and threatening Phi Taus on their patio, right outside the veranda, a brother, Scott Brown, concluding that the unwanted visitor was drunk or high, again told him to leave. Underwood accosted Scott and drew a knife, which another Phi Tau, Danny Baker, promptly knocked from his hand. The intruder picked up his knife and skulked back across the street. Someone at the fraternity house flagged down a campus police cruiser, and an officer went to Gatti’s. The officer encountered Underwood, now accompanied by a new companion, on the bar’s porch, but she then proceeded inside, leaving him behind. With the officer inside the bar, Underwood and the other young man moved toward Lake Avenue.

At this critical moment, Tommy Baer arrived at 1800 Lake. Someone told him what had occurred, so when members saw Underwood, accompanied by the other man, coming back across the street from Gatti’s, Tom took up a position at the house’s rear veranda door. By that time, someone from the house had crossed the street to alert the police officer inside Gatti’s that the man she had passed on the porch was Underwood and that he was now back on the Phi Kappa Tau property. Returning to the fraternity house, the officer went to the west side of the lot, into the darkness between the Phi Kappa Tau and Beta Theta Pi houses, rather than to the busy and lighted east side, where she would have found Underwood wielding a knife.5

Scott Walkup had driven to North Carolina to pick up Ann and bring her to Knoxville for the new semester. They parked in what he remembers as the “primo spot,” at the entrance to the main drive, just feet from the veranda, and were getting out of the car when they saw Tom holding a softball bat horizontally across the door at shoulder level. Underwood came to the door and exchanged words with Tom, who leaned in and quietly said something to the stranger. Scott heard Underwood reply, “You better fucking call the cops then!” As he spoke, and with Scott and Ann looking on in confusion, Underwood struck, lunging at Tom and driving the knife into his chest. Tom cried out, “He’s got a knife! I’ve been stabbed!” and crumbled onto the walkway.

For an instant, all was stunned silence.

“Tom was face down on the concrete,” Scott wrote three decades later. “He went down right before our eyes as we got out of the car. . . I rushed to him and blood was pouring out onto the ground. I asked him what to do (he was the one person there who would know!)” According to later reports, Underwood’s companion picked up the knife, and a brother, Randall, insisting the weapon was “evidence,” demanded he drop it. The stranger sullenly tossed the knife into the grass and went back across the street. Weeks would pass before he would be arrested. One police officer was already on the property, and more, from both the campus police and the Knoxville Police Department, quickly arrived. They took Underwood into custody. Tom, meanwhile, appeared to be dying; still, the ambulance did not come. “He was unresponsive,” Scott wrote. “I took his cap off his head and fashioned it into a pillow of sorts and held him until he drew what was undoubtedly his last breath.” Underwood’s knife had penetrated Tom’s chest cavity, lacerating his aorta. When they finally arrived, emergency medical technicians tried to save him with defibrillation but were unsuccessful. “I remember watching it all in disbelief,” Ann wrote in 2018. “I watched Scott holding Tom’s head. He was so strong.” Now, as the E.M.T.s took Tom to the ambulance, Ann placed her rosary beads in his hands and prayed.

I slept little on Sunday night and studied not at all. Exhausted and emotionally drained, I pushed through my Monday classes on August 22. In the days and weeks to come, I would hear the rumblings of what was to be a remarkable news story. Investigators were misrepresenting the nature of both the gathering at the house and Tom’s final stand at the veranda door. The “second man,” who had accompanied Tom’s assailant to the house on Saturday, was a University of Tennessee football player. Another friend of Underwood’s, taken to the station for questioning, had briefly stolen the knife from under the noses of the campus police on the night of the murder, and though they had no legal authority to do so, the police offered him immunity to get the weapon back. Incredibly, and despite this bumbling, the U. T. Police, barely capable of managing football traffic, had not surrendered the case to the Knoxville Police Department’s homicide bureau. The stories continued to grow and change. These were rumors and portents. Though interesting, they didn’t matter much yet, not to me anyway, and certainly not to my shattered friends at U.T.

All through Sunday and Monday, Knoxville, my friends, and Sheryl beckoned. Alone when I was not in class, I found myself staring at the clock and calculating what time I would arrive in Knoxville if I left at that instant. I did this in reverse too: “If I had left here seven hours ago, I would be sitting with Sheryl right now.” I needed her if I was to get through this. I had James Taylor’s In the Pocket on cassette and listened over and over to “Daddy’s All Gone”:

There's a bus every other hour

There's even a midnight train

But that don't leave me the power

to see your face again

It's not that simple . . .

Finally, telling myself once and for all that I could not possibly leave Memphis, on Monday night I took up a yellow legal pad and composed a letter to the chapter, directing it to my good friend Todd Trapnell, Delta Kappa’s new and now surely overwhelmed president. In it, I explained why I could not come, even to Tom’s funeral, which, I soon learned, U.T. president and former Tennessee governor Lamar Alexander planned to attend. Assuring my friends that I was commiserating with them from the other end of the state, I struggled for a closing. Finally, turning, as I often did for guidance, to American history, I thought of the assassination of President Kennedy, much in the news that summer as its twenty-fifth anniversary approached. Recalling President Johnson’s words on the runway at Andrews that night, after Kennedy’s body was removed from the plane, I wrote in closing: “Do not brood over this; you will find few answers. As was said on the night of another senseless murder a quarter of a century ago, ‘We have suffered a loss that cannot be weighed.'” Brooding, and thus disregarding my own counsel, I dropped the letter in the mail, went to bed, and then tried to get on with my solitary life in Memphis. Some weeks later, I would receive a reply from one of Tom’s closest friends, thanking me for my “encouragement and compassion” and indicating that someone had read my letter, or part of it, at Tom’s rosary service.

In the coming days, as I struggled to focus on my now compromised studies at Memphis State, my friends in Knoxville said goodbye to Tom. The funeral services spanned three days. Wendy Wood-Rowland, then a “Little Sister of the Laurel” (an auxiliary organization whose members were female friends of Delta Kappa), remembers that 1800 Lake “became the gathering spot for fraternity brothers and also family and friends.” They were there, she said, “to reminisce and attempt to come to grips with a tragedy no one could comprehend.” Others came with different agendas. Wendy recalled with some bitterness that “dignitaries,” led by university president Alexander, “arrived to offer condolences” but that they also lectured those present on the dangers of campus alcohol use, this as the mourners, exhausted and bereft, “sat cross-legged on the floor” like children, some not twenty feet from the spot where their sober friend had just died at the hands of a drunk who was not a student and should never have been there. “I have never forgotten how overwhelming that continual grief felt,” Wendy said of the week after the murder.

September came. On the 2nd, Sheryl traveled by bus to Memphis for the long Labor Day weekend. I had seen her only once, on a brief visit in July, since we said goodbye in Greenville on June 6. I picked her up at the Memphis Greyhound station rather late, and I’m sure I lit up when she walked through the door with her suitcase. We were hungry, but many of the nearby restaurants were closed or crowded. Besides, we had much planned, and we both needed to conserve our money. I took her back to my gloomy apartment. There, I shuffled through the stash of random canned goods my mother had sent with me when I left home in August and produced two cans of Campbell’s Chicken and Stars, a children’s soup, really, no doubt purchased with my two-and-a-half-year-old niece, Tim’s daughter Amanda, in mind. We both laughed. I hadn’t laughed in weeks. It would be nice to share hot chicken soup with little stars and be children for a bit.

Basking in Sheryl’s presence and craving firsthand information, as we ate our soup, I asked endless questions, and she struggled to describe what Tom’s death had done to the fraternity—to them all. Sheryl was bright and intuitive. She impressed me with her candid assessment of our friends and their suffering, but her accounts left me deeply concerned. Scott, I knew, was traumatized. I was worried about him. It was not a therapeutic age. Post-traumatic stress disorder was little known or discussed outside a military context, and I really didn’t know how to help. In the face of something so terrible, all one could do was listen, when possible, and try to be a good friend. Even that was not easy. Scott, himself, recently commented that it was a time of expensive phone calls that, as students, none of us could afford to make. “Professional” help, though available, was not promoted then as it would be today. In a recent conversation, Ann wrote succinctly and with regret, “There was no such thing as grief counseling back then.”

In the weeks following Sheryl’s visit, the days became shorter, and the shadows, both real and imagined, became longer. I was not myself. There was no one to talk with except on the phone. I lost weight. I didn’t sleep well and sometimes had nightmares. Often, I heard noises at night. Simple tasks like laundry and washing the dishes seemed impossible. I tried to focus—on school, on the presidential election (a welcome distraction), on the future. Beyond my concern for Scott, Ann, and my other friends, I tried not to think too much about what was happening in Knoxville, though I would know soon enough. On November 5, U.T. would host Boston College for the 1988 homecoming game. It was a dismal season. A pall had fallen over the campus, and football had not been spared. The Volunteers had lost six of their first seven games, defeating, in another ironic twist for me, only Memphis State. I would go to the game, or to Knoxville anyway, see Sheryl and my friends, and try to understand what had happened in August and since.

Ron Powers, a new friend from law school who was also a U.T. alumnus, made the trip with me on November 4. Ron was personable and kind, and I was grateful for his company and his financial help. On the drive, we talked of our undergraduate lives—of our friends, our courses, and our teachers. My mind wandered to Professor Calfee at U.T. and my American literature class of two years before. It was while writing for that class that I had run across F. Scott Fitzgerald’s mournful essay, “My Lost City.” I was strangely drawn to this short piece and had read it a dozen times in two years. Part of an anthology, The Crack-Up, “My Lost City” was a meditation on Fitzgerald’s tormented love for and simultaneous hate for New York. He loved the city because it had made him, because it embodied his loftiest hopes and dreams, and because it seemed everything he had ever wanted. He hated it because he knew that he could never be worthy of it; that its magic was transient, illusory, even; and that he would lose it in the end. I was apprehensive, and the parallels were not lost on me. Fitzgerald loved New York too much, I reflected. You can love something too much.

Knoxville was cool and gray when I arrived at the Phi Kappa Tau house on Friday afternoon, feeling out of place for the only time since I had first set foot there. Though the game was not until the following day, I had expected more activity. Some cars were parked randomly around the perimeter of the lawn, but there were no obvious revelers. I parked on the street, experiencing a brief pang of regret at the loss of my reserved space east of the house. On edge, I bypassed the front door, crossed the patio, rounded the back corner of the veranda, and stood staring at the place where Tom had fallen. June and even August felt like years ago now, and for the first time ever I did not want to go inside. Entering the back door, I walked by my old room and turned right into the hall. It was still afternoon, but the curtains were closed. The house was dingy and dim. A few old friends greeted me enthusiastically, but they wore tired, anxious looks, and though nearly all were in their teens or twenties, they appeared older than I remembered. As always on such occasions, there was the ubiquitous bright orange clothing and regalia, but it seemed incongruous in the gloom.

In the front foyer, one of the active members met me like an underworld doorman in a speakeasy. He welcomed me back but whispered that the university had the house under “scrutiny.” The story of Tom’s death had gone national. ABC’s 20/20 was picking at its edges. U.T. was embarrassed and angry, looking for ways to discredit the fraternity and shift the narrative from campus police incompetence to student irresponsibility. University president Alexander, who had tipped his hand at the house in August, had presidential aspirations on a grander scale, and the casual, campus-wide alcohol use that U.T. had all but ignored for generations was suddenly an emergency. The doors, windows, and curtains were kept shut most of the time, my somber friend explained. No one was to be out of doors with even a cup. There were fewer social events. Everything was tightly controlled.

When her classes ended, Sheryl came to the fraternity house. She knew I was distressed; she always knew. We sat quietly on the front steps, watching the traffic on Lake Avenue as a busy homecoming weekend unfolded. I was contemplative and downcast. My time at the Phi Kappa Tau house that first weekend in November 1988 was disappointing. I went out with Sheryl and some friends, including some fraternity brothers, but for now, at least, the spark that had burned at the corner of Lake and Terrace had dimmed, and this added to the palpable sadness that had hung about me ever since I had moved in early August.

Returning to Memphis on Sunday, I again pondered Fitzgerald and his “lost city.” He and Zelda had left New York at the height of the late 1920s economic boom—at the height of “carnival,” as Fitzgerald called it—when the Jazz Age metropolis pulsed with light and life and seemed a universe unto itself. They were in France and then “somewhere in North Africa” in the autumn and winter of 1929 – 1930, when first the stock market and then the American economy collapsed, Fitzgerald writing that they “heard a dull distant crash which echoed to the farthest wastes of the desert.” Returning home, “in the dark autumn of two years later,” they found a New York that had changed beyond description. “With bowed head and hat in hand,” Fitzgerald wrote, he had “walked reverently through the echoing tomb.”

Had I not just done the same?

“Among the ruins,” he continued, “a few childish wraiths still played to keep up the pretense that they were alive, betraying by their feverish voices and hectic cheeks the thinness of the masquerade.”

Indeed.

Scott Fitzgerald had once written that there were “no second acts in American lives,” and in the dismal winter of 1989 I was inclined to agree with him. However, there were many acts yet to come in the Tom Baer affair, and in my own life, and even in the life of Phi Kappa Tau at the University of Tennessee. As rumored, a few months after the murder, 20/20 came to Knoxville, to the fraternity house, and filmed a full segment on Tom’s death. ABC’s Lynn Sherr interviewed several of my friends, including Scott, on camera. Bob Cheek, a colorful and prominent Knoxville attorney and the father of Rob Cheek, a Delta Kappa alumnus, had conducted his own investigation, concluding that Underwood’s accomplice had indeed been a Tennessee football player, and charged that the university had engaged in a “cover-up” to protect “football interests.” Cheek reported his findings directly to the district attorney, and it was his allegations, all strenuously denied by university officials, that had attracted ABC’s attention. At the very least, 20/20 suggested, the university had behaved incompetently in allowing the U.T. Police to control the investigation (and briefly lose the murder weapon), to the exclusion of the Knoxville Police Department’s seasoned homicide team. On February 10, 1989, having abandoned the law as a career and preparing to return to U.T. for graduate school, I watched the 20/20 segment at home with my parents, introducing them to a central part of my life, a part that, excepting Sheryl and Scott, was all but unknown to them.

As the legal cases unfolded, Jeffrey Underwood’s companion maintained that he had nothing whatsoever to do with the events of August 20 – 21. Though the state charged him as an accessory after the fact, the court dismissed the case. In the years to come, this would be a source of much bitterness among the witnesses, who knew his denials to be lies. More certain was the case against the principal defendant. Many of my friends testified in Underwood’s trial. In the end, a jury convicted him of second-degree murder and two counts of aggravated assault. The court sentenced him to fifteen years in prison but lengthened the penalty by two years because he had tried to smuggle drugs into the jail. By then, though, Bob Cheek was dead of natural causes. He did not live to see the 20/20 segment that exposed his diligent investigative and legal work to a nationwide audience. In gratitude, and with the blessing of the fraternity’s national headquarters, the Delta Kappa Chapter posthumously named Mr. Cheek an honorary brother of Phi Kappa Tau. In 1997, nine years after murdering Tom Baer, Jeffrey Underwood would leave prison on parole, disappearing from the news and, mercifully, from all our lives.

As the fall 1989 semester began, some of the oppressive, unnatural tension that had hung like a shroud over the Phi Kappa Tau house began to dissipate. Still, the ghosts were not easily banished. “What-ifs” plagued Tom’s friends, and some had nightmares. The Cheek investigation scandals dragged on in various forms, and though the enhanced police scrutiny of 1988 slowly diminished, it never really ended. In some sense, the Greek social culture of the entire campus was changed, as was that of the university police. It was over, and it wasn’t over. Late one night, years later, at a Founders Day event in the mid-1990s, Todd Blaeuer and I stood talking by the veranda door. “Sometimes I almost forget it happened,” Todd commented wistfully. “Then you can’t believe it happened. Then you stand outside here, and you know it happened.”

Remarkably, Delta Kappa experienced a renaissance of sorts in the early 1990s. As a graduate student, I was there for some of it, chairing the board of governors, liaising between the chapter and the national office, and, usually with Sheryl at my side, even attending some of the parties. To honor Tom’s memory, the chapter, in 1989, had created the Thomas H. Baer Award for Excellence in Brotherhood, to be presented each year to the new initiate who most embodied Tom’s many fine qualities. His most enduring monument, though, was the “campus safety” movement established by his distraught parents, who lobbied tirelessly and successfully for legislation requiring universities to disclose accurate campus crime statistics to the public. The Baers could have blamed the fraternity or fraternity culture; they didn’t. Throughout the tragedy and its aftermath, they remained supportive friends of Phi Kappa Tau, choosing, I suppose, to remember that Tom’s fraternity friends were suffering too, that Tom had loved Delta Kappa, and that Delta Kappa had loved him.

In the autumn of 1992, four years after the murder, I enrolled in a second graduate degree program at U.T. while working for a non-profit human services agency and searching for teaching jobs in a bad market. I continued to visit the chapter now and then, mostly on game days and special occasions when I might see other alumni. By then, most of Tom’s contemporaries had drifted away. Sheryl, too, was gone. Love can be fleeting and uncertain when you’re in your twenties and the future seems boundless. I had learned, too late I guess, that the future was not boundless, and so I grieved the departure from my life of this bright, funny, and beautiful young woman, who had lighted so much of my considerable darkness. We had shared much, most of it grand but some of it more than a couple so young should have to bear. I loved Sheryl. Her personality had so complemented my own that a mutual friend, Brent Rhymes, once playfully announced, “Here comes America’s favorite couple!” as we walked together across the fraternity house lawn, and at times it almost felt like we were. My companion, my friend, my confidante of three years, Sheryl was my greatest source of strength through my brother’s rapid and horrifying physical decline, and the dark, otherworldly season that followed Tom’s death. I’m sure I never adequately thanked her for any of that—or ever could. It was too late for that now; she was lost to me. That loss marked the close of my youth and would turn my life on end for years to come. Three decades on, I think of her still, wondering how she remembers me, and what, if anything, she retains of those sad, turbulent days.

A few of my other old friends remained in Knoxville. Scott, who had returned to his beloved Memphis, was not among them, though he and I were, and remain, as close as ever. Still, scar tissue has closed over the wounds of August 1988. We speak of them only rarely, and in hushed tones, and I find that our uneasy relationship with those scars is not unique among our friends from those days.

Time passes differently once you’re finally settled. After 2000 came and went, taking my suffering brother with it, the years clicked by like film frames. By 2006, I had long since returned to West Tennessee, was happily married with three children, and had been teaching history for more than a decade, when word came that U.T. had condemned the Phi Kappa Tau house and would raze it to make way for a new parking garage. Threats of this long predated my membership in the fraternity, but this time it was all too real. Other Old Row houses, including those of our neighbors, Beta Theta Pi and Chi Phi, were already gone or were slated for demolition. We had slipped the trap so many times, but our luck had at last run out.

Late in September, I drove to Knoxville for homecoming. All Friday night and into Saturday, torrential rains pounded the city, clogging and overwhelming the gutters and inundating the streets. The weather forced university officials to delay the football game, and impatient fans of the Volunteers and the Marshall University Thundering Herd waded idly up and down the avenues. The Phi Kappa Taus had taken a short-term lease on the temporarily vacated Kappa Sigma house, at the corner of Lake Avenue and Melrose Place, and it was there I found the refugees, huddled in their orange attire, swapping stories in an unfamiliar room where a year ago not one of them would have been welcomed. “Strangers in a strange land,” I mused. Old friends from my era and from even earlier days arrived, and after the game we laughed and talked into the night. Finally, most everyone wandered off to bedrooms or hotels or home, and the Kappa Sigma house was still.

Past midnight, my friend Mike and I walked west down quiet Lake Avenue toward the deserted Phi Kappa Tau house. The streetlights cast blue halos in the fog as we picked our way past the flotsam deposited by the storm. The waters had receded, and a trio of young college girls, out late on a dreary night, giggled past, just as their mothers might have done in the ’80s. At the corner of Lake and Terrace, the site of the old Gatti’s to our backs, Mike and I stood on the soaked and overgrown lawn, moisture clinging to our faces and clothes, peering through the mist at our former home. The old house stood stark and unfamiliar. Most of the windows had been boarded over from the inside, but something else was different too: something was missing. Presently, I realized the letters were not there. The “Harvard red” letters—Φ, Κ, and Τ—each more than a foot high, were gone, rightfully claimed as mementos by some lucky brother, leaving ghostly, gray impressions in the places where they had hung for decades.

University officials had told our members to stay out of the house. Mike ignored the warnings and went in anyway, saying he would be a few minutes.

My business was outside.

For a time, I sat in the dark on the wooden deck, my elbows on my knees, gazing longingly at the concrete patio and remembering the years of laughter and fun there: the dances, the mixers, the homecoming floats, the ill-advised homemade swimming pool, the “one-man band.” Images of old friends and a lost love moved before me, and I perceived, for an instant, that I could reach out and touch them if I wished. Finally, my reverie broken by the returning drizzle and the sounds of Mike moving through the house, I stood and rounded the rear corner of the veranda, to stare, one last time, at the remains of the walkway where, eighteen years earlier, Tom had drawn his last breath in Scott’s arms. In my mind, I had watched it all unfold a thousand times. So many times I had wished I had been there to stop it. Now, though, in my last stolen moment in this place, the pain borne by Scott, Ann, and the other witnesses crowded in on me, dissipating my conceit and revealing a truth I had shunned for nearly two decades: I wasn’t special. My friends couldn’t stop it, and I couldn’t have stopped it either. There was nothing I could have done. Nothing. “I’m glad I wasn’t here,” I finally admitted to myself, choking back unaccustomed tears in the rain. “I’m thankful I was spared.”

The house would be gone within a few weeks, maybe sooner, and I knew I would never see it again. From Miami University in Ohio, Phi Kappa Tau’s national office had issued the traditional upbeat talking points it reserved for chapters losing their homes: A fraternity can recruit and survive without a house. This is a growth opportunity. This is just the beginning for Delta Kappa.

It wasn’t a beginning. It was the end. I knew, and I knew why. The little I retained of religion could be reduced to one simple proposition: “blood sanctifies.” This was hallowed ground now, and we were each a part of it, as it was a part of each of us. The Delta Kappa Chapter of Phi Kappa Tau had somehow become one with this old red and white house, perched for some eighty years on its emerald lawn at the corner of Lake and Terrace Avenues. Were it not true before, it had become so on a warm summer night long ago, when innocent blood ran across these same gray stones and Ann Langdon placed her rosary beads in Tom Baer’s hands.

Mike came out of the house with tears in his eyes. Clearly, we had been on different but not dissimilar journeys. We said little, but looked one another in the face with that silent understanding that passes between old friends in sad times, when there is really nothing more to say. Then we turned, crossed Terrace Avenue in the rain, and walked east into the shrouded night.

A couple of years after the University demolished 1800 Lake, the discouraged undergraduate officers notified the graduate council and the board of governors that they wished to suspend operations, and Phi Kappa Tau ceased to exist as an undergraduate organization at the University of Tennessee. All our hearts were broken, though inwardly I thought it remarkable that Delta Kappa had survived Thomas Baer by two decades. “It had to end this way,” I thought to myself, looking back on all that had happened. “It was foreordained.” And though I mourned the institution that had given form and purpose to my young adult life, it seemed right and fitting, somehow, that the senseless, empty death, a generation earlier, of a single first-year member would now be fixed like a constellation in its place and would forever stand, unchallenged, as the central event in its history.

KTB: August 2018