My parents were strict.

During my early teen years, I went places with my older brother, who could drive, or—rarely—with a cousin or family friend. If I wanted to do anything with my peers, though, it had to be school-related, which explains why I spent so much time at basketball games and other school events. They were my social outlet.

The first instance I can recall of getting into a car driven by one my own friends and going anywhere without adults was when I was 15, in the hot, drought-scorched summer of 1980, when Marion Eugene “Skeeter” Mallette pulled his pampered and souped-up Chevy Chevelle into my drive, to take me not to some happy, parent-free event, but to the funeral of our classmate, Chris Bollen. On July 4, Chris had fallen out of a boat on Kentucky Lake (boating with friends was exactly the kind of thing you would never have found me doing at 15) and was struck by the propeller. It was days before searchers found her. Neither Skeeter nor I was particularly close to Chris. She was lovely, and had blue eyes of the sort that are now Photo Shopped onto makeup ads, so, even though we shared a table in one class, I doubt she could have called me by name (Skeeter she would know). Still, her death traumatized my friends and me, the first loss of its kind we experienced. Only with reluctance did my dad consent to let me attend the funeral with my good friend, whom he viewed with some suspicion.

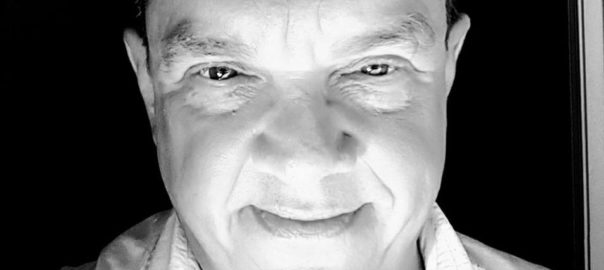

Continue reading Marion Eugene “Skeeter” Mallette: In Memoriam