Eight Lost American Presidents and the Worlds They Knew

Background

Last night, I lay awake thinking, as I often do, about intricate details of American presidential history.1 This odd pastime helps me fall asleep. It occurred to me that I am nearly 60, and no incumbent American president has died in my lifetime. Indeed, we are currently in the longest sustained period of presidential “survival” (for want of a better word) in our history. This is good, of course, whatever your opinions of recent chief executives, but I wonder if people realize what a historical aberration it is. With the oldest president in our history about to pass the office to the oldest person ever elected to a presidential term, I thought it worthwhile to examine the fates of the presidents who did not survive the office, the lives they knew toward the end, the events that led to their deaths, and how common that outcome once was.

It was probably fortunate for the sustainability of our institutions that the presidents of the first half-century all managed to survive their terms. There had been close calls. Twice, George Washington nearly died of illness. James Madison survived a severe intestinal infection, what was then called bilious fever, that could easily have killed him in those days of primitive medicine. Andrew Jackson, who was, it seems, always at death’s door but wouldn’t pass through, survived an attack by a deranged man who fired not one but two pistols at him, both of which misfired. Despite these near misses, until 2015, this opening interval was the longest in our history without a presidential death.

Of the 45 men who have served as president, eight—nearly a fifth—died in office. Half of the eight were homicides. That seems like a lot in a western democracy. Indeed, once the phenomenon began, presidential deaths were surprisingly common, and the intervals between these national tragedies were, on average, quite short.

The Untried Engines of Succession:

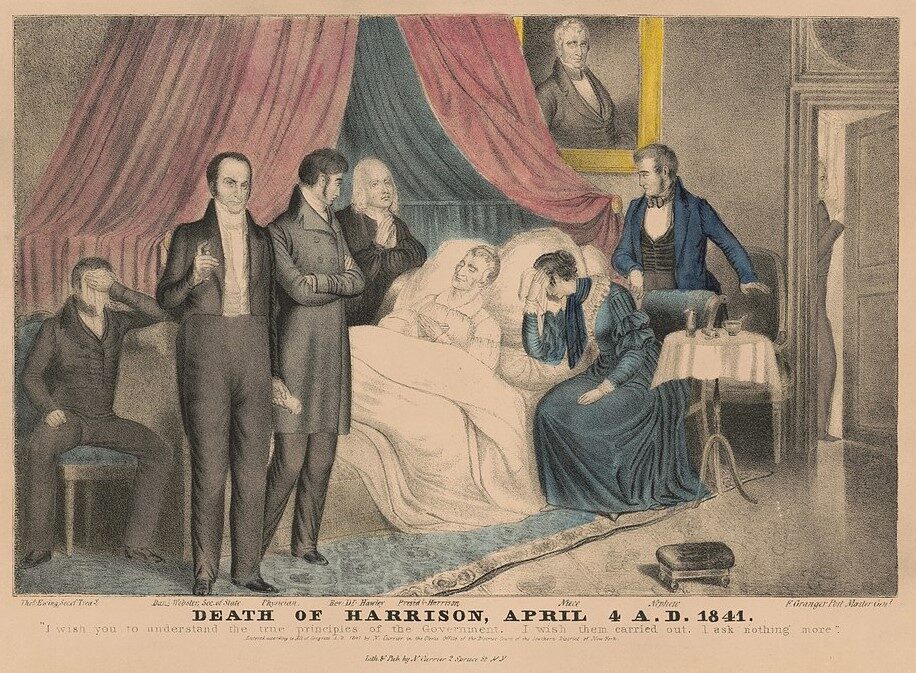

William Henry Harrison, April 4, 1841

Things got off to a good start. Fifty-two years passed between the inception of the Constitution, in March 1789,2 and the death, in April 1841, of William Henry Harrison,3 the ninth president. Harrison was the first president elected by the Whigs, a party established to challenge Andrew Jackson. The Whigs rejoiced at Harrison’s election, believing he would end a dozen years of Democratic hegemony. They were to be sorely disappointed.

Harrison moved into the White House on March 4, 1841 and passed the first days organizing his new life there. Then, on March 26, he sent for a physician, Dr. Thomas Miller, and indicated he had not felt well for several days. His condition improved a bit, then declined. By April 1, he was bedridden, probably with pneumonia. Harrison’s illness, coming so soon after his inauguration, sparked many myths and legends. It is commonly said that he caught cold while delivering a two-hour inaugural address without an overcoat on March 4. While it is true he did not wear a coat and that the speech was long—the longest in inaugural history— there is no clear evidence that this caused his sickness which, after all, did not become a concern until three weeks later. Many popular writers, perpetuating legends from secondary sources, have bolstered the “inaugural cold” story by misrepresenting the weather conditions in Washington on March 4. Some accounts say Harrison made his speech in the rain, some in driving rain, others in sleet. It was cool and windy; that is not in dispute. However, one witness said the weather was “beautiful,” while Washington journalist Benjamin Perly Poor stated that “the weather was mild and the streets were perfectly dry.”

The president’s activities later in the month, prosaic and difficult to document, are no less disputed. Some say he went for a haircut and walked home in the cold without a hat on March 25. One colorful legend describes Harrison walking to the local vegetable market, basket in hand, on March 27 (despite having consulted with his doctor the previous day), with some adding that he was caught in a cold rain on the way home. He may have gone for a walk (some counter even this, arguing that he had already abandoned his walks due to excessive attention paid to him on the streets), but neither the rain nor the vegetable market story can be confirmed.

One thing we know for certain about Harrison’s brief tenure in the White House is that it was mostly unpleasant. His wife Anna was absent. She was still in Ohio, preparing to move to Washington to join her husband later in the spring, when better weather would make riverboat and rail travel easier. Political stresses were his greatest burden. Powerful Whigs, starved for patronage, despised the Jacksonian Democrats, and in that age of the “spoils system,” before civil service came to the federal government, were counting on Harrison to “turn them out”—fire them en masse—all the way down to local postal workers, and replace them with loyal Whigs, regardless of qualifications or ability. Harrison refused, calling such a proposal “iniquity,” and had a written altercation with the great Henry Clay, who had expected to control presidential power through him. The clamor for patronage also led, as it had for previous presidents, to swarms of office seekers who harassed Harrison day and night. In a letter to his sister, the president stated, bluntly, “They pursue me so closely that I cannot even attend to the necessary functions of nature.”

Whatever the cause, by April 2, Harrison’s condition was grave. After enduring days of almost barbaric (even by 1841 standards) medical treatment at the hands of Dr. Miller and others, he mumbled that he wished to be left alone and then died, shortly after midnight on April 4. He was 68.

Harrison had served only 30 days, and his death was a severe jolt to the nation and to the powerful men who now confronted the Constitution’s ambiguous presidential succession provisions. They had never been tried, and they might not work. John Tyler, the determined vice president, a sort of Democrat in Whig clothing who receives credit for little else, made the best of the situation by firmly insisting that he was the president and getting away with it. Tyler thus thwarted the designs of some of the most ambitious men in our history, who were intriguing, behind the scenes, to consign him to a type of caretaker status.

The laws of presidential succession were contradictory, confusing, and atrophied in 1841. Almost anything might have happened: a power struggle within the cabinet, a special election, a weak “acting president” dominated by others. Harrison’s death, so early in his term, and Tyler’s determined claim to the presidency set a precedent, clarifying procedures for the future and safeguarding the independence of the executive branch. This precedent would serve the American people well in the years to come.

Interval from the commencement of government under the

Constitution to the death of William Henry Harrison:

52 years, 1 month

Iced Milk and Cherries:

Zachary Taylor, July 9, 1850

The death of “Old Tippecanoe” Harrison, the first Whig president, was followed, a mere nine years later, by the death of the second and last elected Whig president, Zachary Taylor. Disappointed as the Whigs were by Harrison’s death, it seems surprising that they turned, in 1848, to another aging and rather haggard general with uncertain political principles. Indeed, after Taylor became president-elect, James K. Polk, the outgoing Democratic president, invited him to the White House and found him ignorant of public policy and wholly unprepared for the difficult task ahead. Not surprisingly, then, as they had with Harrison, the pressures of the job quickly began to weigh on Taylor. No photographs of Harrison are known to exist, but Taylor did sit for a number of Daguerreotypes, one of which shows an obviously tired and unhealthy, perhaps even dying man. Though he was but 65 years old, he could easily have passed for 75 or even older.

Taylor was a tough old general, but he was in over his head in Washington. The Mexican War and the California Gold Rush had reignited the old question of slavery in the western territories, and the bluster of Southern secession was in the air. The central legislative issue of the time was the “Omnibus Bill,” which would later evolve, in modified form, into the Compromise of 1850. Crafted by Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, this series of proposals, combined (at first) into a single package, was designed to settle the major slavery-related issues between North and South and avert civil war. Though he was a Southern slaveholder, Taylor opposed the spread of slavery into the West, and he wanted to admit California into the Union immediately, as a free state, bypassing the territorial stage and thus shutting Congress and the “Slave Power” out of any future decisions concerning slavery there. California was growing rapidly due to the Gold Rush. It needed government, and its population had demonstrated its opposition to slavery. Though Whigs had created their party explicitly to combat Andrew Jackson and Jacksonianism, when Southern “Fire-Eaters” began suggesting they might secede from the Union and raise their own troops, Taylor took a decidedly Jacksonian stand, threatening, as Jackson had during the Nullification Crisis of the 1830s, to personally lead the Army into the South, crush disunion there, and hang those “taken in treason.” According to one account, the president drove a delegation of Southern leaders from the White House, shouting from the top of the stairs that he would hang Southern traitors as readily as he had “hanged spies in Mexico.” The stresses on the aging president’s health must have been profound.

With debate over the compromise measures raging in the Senate, Taylor, on July 4, 1850, attended a cornerstone ceremony for the Washington Monument. He became overheated, returned to the sweltering White House, and, according to legend, gorged himself on “iced milk and cherries.” Some have questioned whether “iced” milk would have been available in July in the Washington of 1850, but the White House did maintain an icehouse and had since Jefferson’s day. Other accounts say Taylor simply ate cherries or “fruit.” Whatever he ate, the president soon developed a severe intestinal illness, apparently gastroenteritis, though it could well have been something more serious and more infectious. The White House summoned Dr. Miller, the same physician who had treated President Harrison nearly a decade earlier. Although the Boston Medical Journal, a forerunner of the New England Journal of Medicine, had come close to accusing him of killing Harrison with his archaic and unfocused “remedies,” Miller was now once again at the side of a critically ill president. Taylor died on July 9, 1850, a mere 16 months after taking office. He was 65 years old. His doctors finally concluded that he had died of “cholera morbus,” one of many almost meaningless nineteenth century medical terms. It encompassed a variety of gastrointestinal maladies but did not imply genuine “cholera” of the type that had already killed Taylor’s predecessor, James K. Polk.

For nearly a century and a half, rumor swirled that Zachary Taylor’s fellow southerners had poisoned him with arsenic to remove him as an impediment to the Compromise, or, should compromise fail, to southern secession. After the Civil War, one story even had Mississippi senator and later Confederate States president Jefferson Davis poisoning him. Davis was Taylor’s former son-in-law, having once been married to his daughter Knox, who had died of malaria only months after their wedding. In the 1980s, Clara Rising, a former University of Florida professor who had become convinced that the rumors of Taylor’s murder were true, began a campaign to have his remains exhumed and tested for arsenic. She convinced Taylor’s closest living relative to cooperate, and in July 1991, Kentucky officials opened the tomb and removed the coffin. The state coroner supervised as hair and nail samples were taken from Taylor’s body, which was then reinterred with military honors. Testing at Oak Ridge National Laboratories found no evidence of poison; the arsenic levels in Taylor’s remains were within normal limits. To her credit, Clara Rising accepted the findings, as to arsenic, but she remained convinced that “Old Rough and Ready” had been poisoned with something.

On Taylor’s death, Vice President Millard Fillmore, a New Yorker, became president. Fillmore had warned Taylor that if the Compromise of 1850 should receive a tie vote in the Senate, he, as president of the Senate, would break the tie in its favor. Taylor’s opposition and veto threats had frustrated Henry Clay’s original version of the proposal. Now, with the support of Fillmore, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois ushered Clay’s compromise through in pieces, rather than as a single bill. Eager to calm the growing sectional tensions, Fillmore quickly signed the bills, including the hated Fugitive Slave Act. In doing so, he delayed the Civil War by a decade. Tragically, he may also have made it inevitable.

Interval from William Henry Harrison’s death to the death of Zachary Taylor:

9 years, 3 months, 5 days

“Who is Dead in the White House?”

Abraham Lincoln, April 15, 1865

The sectional catastrophe that James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, Zachary Taylor, and Millard Fillmore sought to avert came in 1860, with the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency. On the pretense of protecting slavery from the “Black Republicans,” seven states of the Deep South declared secession from the Union, just as Jackson had long ago predicted they would. By spring, they had formed the Confederate States of America, had written a constitution, and had elected a congress and a president. On April 12, 1861, South Carolina militia fired on United States troops on what they considered South Carolina soil: Fort Sumter, a United States Army fort on an island in Charleston Harbor. When Lincoln, only five weeks in office, called for volunteers to suppress the “rebellion,” four states of the Upper South adopted ordinances of secession as well. “The tug,” as Lincoln had put it, had come.

For nearly four years, Americans slaughtered each other in vast numbers, while Abraham Lincoln struggled to keep the ship afloat.

Believing the North would lose the war if the Border States, the four loyal slave states of Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware should secede, in the beginning, Lincoln steadfastly insisted that the North was fighting to preserve the union of the states, not to undermine or destroy slavery. Like most Republicans, Lincoln believed that slavery was a state phenomenon and that neither he nor Congress had power over any aspect of it in the states where it already existed. Republicans also believed, however—and this was their central political belief—that Congress had absolute power to regulate slavery within the federal territories and should keep slavery out of the West so it would eventually wither and die, even in the South.

As the war went on and on, however, and as the numbers of dead and wounded mounted, Lincoln began to refine his thinking. By the middle of 1862, with the war in its second year, he had concluded that the existence of the rebellion against federal authority empowered him, as commander-in-chief, to take extraordinary action to secure victory. As a “war measure,” he would use this power to strike at the heart of the Confederacy by attacking slavery itself. On September 22, he issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, stating that on January 1, 1863 he would declare all slaves free in places still in rebellion against the authority of the United States. Slavery in places not in rebellion, including in the Border States and areas already conquered by the Union Army, would not be affected. Lincoln gave the Southern states 100 days to stop fighting and abandon secession; those that did would be accepted back into the Union with slavery intact there. After 100 days, emancipation would become official United States political, legal, and military policy in all areas still in rebellion. Those places would be conquered over time, however long it should take, and their slaves would be freed.

No state took the president’s offer. On January 1, 1863, Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring nearly all slaves throughout the Confederacy free in the eyes of the United States Government. The Proclamation did not impact the Border States, occupied Tennessee, or several occupied parishes in Louisiana. Few slaves were, therefore, freed at first, but Lincoln had transformed the struggle into a war for union and against slavery, and after the Proclamation, everywhere the American flag went at the head of a conquering Union army, emancipation went with it. The South denounced the Emancipation Proclamation as a monstrous act intended to foment servile insurrection. It angered many Northerners as well. Throughout the country, there were those who came to hate Abraham Lincoln with a new vehemence.

There were not a few who wanted to kill him.

From the moment he began running for president, Abraham Lincoln received death threats. When Pinkerton detectives discovered a highly credible plot to kill him before the inauguration, in 1861, he had to sneak through Baltimore in disguise to reach the capital and assume the presidency. The plot was real, but the story of his late-night entry into Washington reached the press, humiliating him. Thereafter, he said little about his own safety, except to dismiss most well-meaning attempts to secure it. He famously kept a fat envelope of written threats in a pigeonhole in his desk, stressing to others that his wife, the high-strung Mary Todd Lincoln, must know nothing of them. Still, even Lincoln was rattled one summer night in 1864, when someone shot his hat off his head, as he rode alone through the dark to the Soldiers’ Home, his summer retreat on the edge of the city.

As the 1864 presidential election approached, Abraham Lincoln had little hope of reelection. As Lincoln, himself, would later observe, the war had far exceeded the magnitude and the duration most people, including he, had anticipated in 1861, and hundreds of thousands were dead. Some northerners were unhappy to see a struggle initiated to preserve the Union transformed into a war to end slavery, and some no longer wanted to fight. Conversely, with emancipation now official Union policy, many southerners were prepared to fight to the last man. With the war in its fourth year, there was no end in sight, and the summer of 1864 was the nadir of Union fortunes. Facing defeat at the polls, Lincoln now crafted a contingency plan for working alongside the new president-elect to save the Union prior to his departure from the White House, fearing, as he stated bluntly to his cabinet, that the new president would “have secured his election on such ground that he can not not possibly save it afterwards.”

Changes were coming, however. In August, Union general William Tecumseh Sherman captured Atlanta and began laying waste to Georgia and South Carolina. Lincoln’s prospects for reelection improved, and in November he handily defeated his former top general, George B. McClellan, whom he had twice fired. After Lincoln’s second inaugural, on March 4, 1865, events accelerated. On April 3, Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital, fell to Union forces. On April 9, Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant. On April 10, celebration erupted among Unionists in Washington, while the city’s large pro-Confederate population quietly nursed their grievances.

The celebrations were short-lived. At around 10:15 P.M. on April 14, John Wilkes Booth, a prominent actor who was also a fanatical southern partisan and a white supremacist, shot Lincoln in Ford’s Theater on Tenth Street. Unconscious, Lincoln was taken across the street to Petersen’s Boarding House. His bearers placed him on a bed where John Wilkes Booth, himself, had once lain while visiting a friend. Lincoln died the next morning at 7:22. He was 56. Vice President Andrew Johnson, who, like Tyler before him, was at heart a Southern Democrat, took the presidential oath of office a few hours later. For the third time in 24 years, an American president had died in office, but this time he had been murdered.

Others would follow.

Interval from Zachary Taylor’s death to the death of Abraham Lincoln: 14 years, 9 months, 6 days

“Arthur is President Now!”

James A. Garfield, September 19, 1881

With victory in the war, the accompanying destruction of slavery, and the mystique of the martyred Lincoln, an era of near-total Republican ascendancy arrived. Only one Democratic candidate, Grover Cleveland (twice, but in non-consecutive elections), would become president between 1869 and 1913.

In 1880, in an election that marked the closest popular vote difference in American history—fewer than 2,000 votes out of millions cast—Ohio congressman James A. Garfield defeated his fellow Union Army veteran Winfield Scott Hancock. In March 1881, Garfield, his wife Lucretia, and their boisterous children moved into the presidential mansion. Though the Garfields were an affectionate, energetic lot, according to William Seale, the preeminent historian of the White House, Tommy Pendel, the longtime presidential doorman known for his remarkable memory, would, “as an old man,” recall them as “only shadows.”

On July 2, 1881, less than four months after the inaugural, Charles Guiteau, a ne’er-do-well political intriguer with a long history of mental illness, shot President Garfield in the lower back, in the lobby of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington. Guiteau had written, called upon, and otherwise harassed the president for months, once even securing a brief audience with him. He had convinced himself that one pathetic and widely ridiculed speech he had delivered on Garfield’s behalf during the campaign had guaranteed Republican victory. Guiteau sought appointment as the United States consul to Paris, a post for which he had no qualifications. Indeed, he was not qualified to work in, let alone run, an American consulate. In June, realizing Garfield would never reward him for his efforts, Guiteau resolved to murder the president. He purchased a gun, a .44 caliber British Bulldog revolver with ivory handles. The Bulldog would, he said later, look good in a museum someday. Reasoning, as only a mentally ill person could, that a grateful Vice President Chester A. Arthur would free him from jail and then reward him with appointment to the Paris consulship, as he fired on Garfield, Guiteau shouted, “Arthur is president now!”

Thus began an eighty-day national nightmare, as Garfield, incised, prodded, probed, and argued over by his physicians, including the glory-seeking Dr. Doctor Willard Bliss (“Doctor” was his actual given name!) suffered through one of the hottest summers in memory. Several times, the president had asked to be taken to the New Jersey Shore, that he might die in peace amid the gulls and sea breezes. The autocratic Bliss had denied each request. In September, Garfield demanded to be taken there. He was. In a touching tribute, the citizens of Elberon, New Jersey spent the night before his arrival building a railroad spur to the door of his cottage, so the president could be moved from his train to his new bedroom, overlooking the beach, with as little disturbance as possible.

President James A. Garfield died in his cottage at Elberon late on the night of September 19, 1881. He had served as president only for a little more than six months, and, since he performed virtually no presidential duties after the shooting on July 2, he was active as president a bit less than four months. Garfield’s presidency remains, to this day, the second-shortest in our history. Only 49 at his death, not until John F. Kennedy’s assassination, 82 years later, would a younger man die in the presidential office.

Interval from Abraham Lincoln’s death to the death of James A. Garfield: 16 years, 5 months, 4 days

“His Will, Not Ours, Be Done.”

William McKinley, September 14, 1901

William McKinley was the last of five brave Civil War veterans who served as president. By many accounts, his most appealing human characteristic was his sincere kindness. Few people ever had a bad word to say about him personally, and his patient care for his chronically ailing wife, Ida, was legendary. McKinley entered the White House in a time of rapid change for the United States. His opponent in both the 1896 and the 1900 elections was the “Great Commoner,” William Jennings Bryan, champion of a simple, upright, rural, and agrarian America—itself something of a national myth—that was rapidly receding into the past. Before McKinley’s first term was half over, the United States, still largely aloof from the Great Powers’ intrigues and imperial ambitions in 1896, would emerge as a world power and would itself establish an empire stretching from the Florida Straits to the Philippine Sea.

It was the era of the anarchist. In the 1890s alone, anarchists had murdered the president of France, the prime minister of Spain, the empress of Austria-Hungary, and the King of Italy. The United States was not to be spared. In September, the McKinleys traveled to Buffalo, New York to attend the closing days of the Pan American Exposition, one of many “world’s fairs” of the time and one of the most elaborate. On September 6, 1901, only six months after the beginning of his second term, President McKinley was shaking hands in a receiving line in the fair’s Temple of Music. A nervous man with a seemingly bandaged hand approached. It was Leon Czolgosz, a 28-year-old Ohio laborer who had become a follower and admirer of American anarchist leader Emma Goldman. Czolgosz had concealed a revolver in a handkerchief. He fired into McKinley’s abdomen. The bullet perforated both the anterior and posterior walls of the president’s stomach and buried itself in the muscles of his back.

Taken to the home of the Pan American Exposition’s president for surgery and recovery, McKinley seemed to rally. Within a few days, infection required a second surgery, and doctors found a piece of fabric from his clothing in the wound. The incision became gangrenous. William McKinley died in Buffalo on September 14, 1901, just five days short of 20 years since the death of James Garfield. He was 58 years old.

Interval from James A. Garfield’s death to the death of William McKinley: 19 years, 11 months, 26 days

“One of Nature’s Noblemen”:

Warren G. Harding, August 2, 1923

After William McKinley’s death, two tumultuous decades followed, years in which the United States consolidated the gains it had acquired at the end of the 1890s, emerging, at last, as the equal of the Great Powers. In 1914, the World War erupted in Europe, quickly engulfing nations great and small, and spreading, to different degrees and in different ways, to colonies around the globe. By the end, seven-eighths of the world’s people would choose sides, and three of its principal empires, those of Germany, Russia, and Austria-Hungary, would collapse. In 1917, President Woodrow Wilson would lead the United States into the conflict, to break the deadly stalemate in favor of the Allied Powers. When the Allies emerged victorious, 20 months later, the United States was their unofficial leader, the most powerful and respected nation on earth.

Many Americans were not ready for the mantle of world leadership their idealistic president and his “war for democracy” thrust upon them. Demobilization brought economic, racial, and social problems, as well as the inevitable accounting of the dead and wounded. Disillusionment spread. President Wilson’s dream of a world led by the United States and the other Allies, through the mechanism of the League of Nations, came to nothing, when the Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles upon which the League was founded. Wilson all but killed himself trying to rally the public to the cause, but it was too late. In September 1919, he suffered a devastating stroke that left him physically disabled, and, for a time, mentally incapacitated.

The world did not stop. The public was exhausted by the war and its aftermath. The Republican Party was certain of victory in 1920. Former President Roosevelt would probably have been the nominee and the victor, but he had died in January 1919, leaving an open field. That summer, the Republicans nominated Ohio senator Warren G. Harding, who decisively defeated Wilson’s handpicked candidate, James Cox. Harding was a small-town newspaper editor from Middle America. Handsome, amiable, somewhat roguish, he was unschooled in the ways of international diplomacy, at a time when the presidency had risen to the pinnacle of world affairs. The demands and security requirements of the presidency, combined with the domestic stresses imposed by Florence, his matronly and overbearing wife, whom he called the “Duchess,” cut Harding off from his personal concerns and pleasures. He enjoyed leisure travel and poker with his friends, both of which became more difficult. He was also managing many secrets, including serious scandals within his official family; at least two mistresses, one of whom had recently borne him a daughter he had never seen but was supporting; and his own compromised and deteriorating health.

Pressured by his wife and friends to run for a second term in 1924, in June 1923, Harding, Florence, and a large entourage left Washington for a cross-country odyssey, by rail and sea, to Alaska, where no American president had ever set foot. Despite the luxury train car, the trip was exhausting in the summer heat. The president rarely rested. He was already known to sleep sitting up in bed because he had difficulty breathing while lying down. There were signs throughout the trip that he was failing. At one stop, he had to climb a long flight of outdoor steps. He would climb a few, then stop to “enjoy the view.” He seemed, really, to be catching his breath. The ceremonial driving of a railroad spike in Alaska exhausted him.

The trip planners had arranged for Harding to tour the West Coast on his way south after leaving Alaska. From Southern California, he would travel by ship through the Panama Canal and return to Washington. In late July, Harding grew seriously ill in Grant’s Pass, Oregon. The White House canceled the remainder of the journey, and the party diverted to San Francisco, checking into the Palace Hotel. Resting in his bed as his wife read to him, Harding died suddenly in the early evening of August 2, 1923. He was simply there one instant and gone the next. No other American president died so instantaneously. He was 57 years old.

Interval from William McKinley’s death to the death of Warren G. Harding: 21 years, 10 months, 19 days

“The Hope of All Peoples in an Anguished World”:

Franklin D. Roosevelt, April 12, 1945

The early 1920s were devoted to demobilization and readjustment. The return of peace brought recession, strikes, and protests, but these were followed by an unprecedented economic boom. It was an orgy of unchecked production and consumption that improved the lives of millions but alienated farmers and the very poor, who did not share in the bounty. Much of the prosperity was, in fact, illusory. The catastrophic stock market crash of October 1929 did not cause the Great Depression that followed—at best it was a signal of the Depression’s arrival—but that did not seem to matter. The Great Depression came, and in 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the defeated Democratic vice presidential candidate of 1920, was elected to the presidency to do something about it. In 1921, after the election loss as Cox’s running mate, Roosevelt had been stricken with polio, which left him paralyzed from the waist down. He had spent years fighting his way back from despair before being elected governor of New York. When the Great Depression undid President Herbert Hoover and the Republican Party, Governor Roosevelt seemed to many to be the savior of the nation.

Franklin Roosevelt fought the Great Depression through two presidential terms, and in the process changed the nature of the United States government and its relationship to its people. By the time the economy began to recover and the end of his second term approached, in 1940, war had again broken out in Europe and Asia. Faced with the prospect of leaving office with the Depression still not solidly beaten and a second world war threatening to engulf the United States, Roosevelt broke all historical precedent by running for and winning a third term. Eleven months into that term, the Japanese attack on the Pearl Harbor navy base in Hawai’i left the United States at war with Japan, Germany, and Italy.

For nearly three years, Roosevelt struggled to rally the American people, the American military, and his fractious allies. As the prospects for victory and peace rose, his health, already severely compromised, deteriorated. His muscles were growing weaker. Worse, the heart disease he had presumably inherited from his father, probably aggravated by years of smoking and stress, worsened into congestive heart failure. After the Allied invasion of France in 1944, it became clear that the end of the war in Europe was only months away, but so was the end of Roosevelt’s third term. Eager to see the European war through, and not knowing how long the war in Asia would continue, Roosevelt, despite his poor health, decided to run for a fourth term. This decision was controversial, especially among those who knew of his condition, but he easily won the election in November.

On January 20, 1945, Roosevelt took the presidential oath of office for a fourth time. For the first time since 1817, the public inauguration of a regularly elected president was held away from the Capitol. Roosevelt swore the oath in a small ceremony on the South Portico of the White House. Ostensibly, this was a cost saving measure due to the war. More likely, it was to spare Roosevelt the pressure and the stress of a full ceremony. Shortly thereafter, the president left for Yalta in the Soviet Union.

Roosevelt flew to the Black Sea resort of Yalta, in the Crimea, to confer with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin. Compared to today, presidential air travel offered few comforts in 1945, and it must have been exhausting for a man in Roosevelt’s condition, let alone one traveling through a war zone. For a week, the three Allied leaders conferred, argued, and negotiated, to determine the terms of the war’s end and the structure of the postwar world.

Roosevelt returned home in February, and on March 1 addressed Congress. Legislators were shocked at the president’s appearance. His face was so drawn and gray that he was barely recognizable as the F.D.R. of 1933, or even of 1943. Throughout the address, between witty comments and smiles, he seemed to suck in and force out air and wiped his mouth with a handkerchief. Most surprisingly, The president addressed the lawmakers sitting down. He drew attention to this in his first sentence, asking their pardon for his “unusual posture.” Then the president said, “I know that you will realize that it makes it a lot easier for me not to have to carry about ten pounds of steel around on the bottom of my legs.” This was the first time Roosevelt had ever publicly acknowledged his disability or openly expressed any discomfort associated with it.

In April, Roosevelt, exhausted, repaired to the “Little White House,” his cottage at Warm Springs, Georgia, where years ago he had established a treatment center for those, especially children, stricken with polio and similar illnessess. On April 12, as he posed for a portrait by a Russian painter, Elizabeth Shoumatoff, Roosevelt read and sorted his mail. Suddenly, he put his fingers to his temples, said he had a terrible headache, and collapsed. He died in his bedroom at the cottage a few hours later. Though by then he could have easily passed for 75, he was only 63 years old.

Interval from Warren G. Harding’s death to the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt: 21 years, 8 months, 10 days

“And We Are All Mortal.”

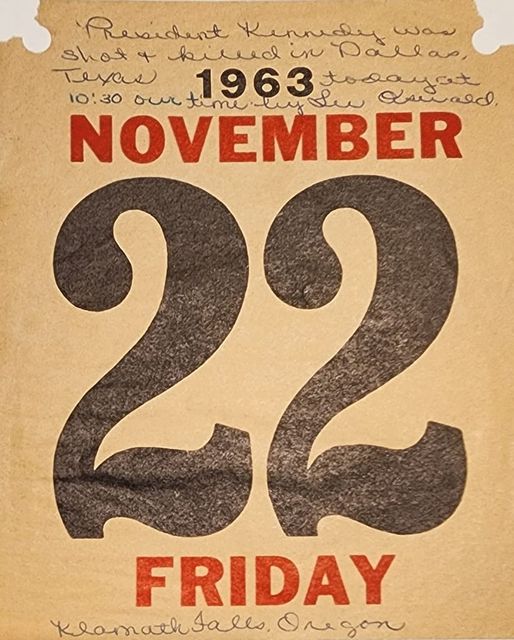

John F. Kennedy, November 22, 1963

On the day Franklin Roosevelt died, he had been president for just over 12 years. By the time his successor, Harry Truman, finished Roosevelt’s term and completed one of his own, Democrats had occupied the White House for two decades. In 1960, after an eight-year period of Republican rule under Dwight Eisenhower, the Democrats again captured the prize with the election of John F. Kennedy, a Massachusetts senator from a prominent Irish Catholic family.

When he assumed office on January 20, 1961, Kennedy was only 43. He was not the youngest president—that distinction belonged to Theodore Roosevelt, who was 42 when he acceded to the presidency following McKinley’s murder—but he was the youngest person ever elected to the office. His youth, his good looks, his wit, and his carefully stage-managed public family life endowed him with an aura of “vigor” (a favorite Kennedy family word) and robust health. Much of this image was fiction; in reality, Kennedy had been sick much of his life. Lyndon Johnson of Texas, Kennedy’s rival for the presidency, who would become his vice president, once allegedly ridiculed him behind his back, saying the younger man looked as though he had rickets.

Kennedy’s debilitating back condition was known to the public, but they tended to pass it off as the “backache” of an otherwise active and energetic man, moving into middle age with a symbolic battle scar. Kennedy did indeed have a scar, but it was a real one, for his condition was far worse than most people knew, and in the 1940s he had endured serious back surgery, which required a long recovery and was mostly unsuccessful. Though the public and the press commiserated with the president over his back, and many found his quaint presidential rocking chairs charming, very few people knew of the president’s more serious health problem. He suffered from Addison’s disease, an adrenal deficiency, considered dangerous or even deadly in the 1960s, for which he was constantly medicated. It is now well established that Kennedy, by the end of his life, was receiving daily injections for both his back and his adrenal deficiency and found it difficult to function without them.

In the autumn of 1963, with the 1964 election only about 11 months away, Kennedy was popular, but not popular enough to guarantee reelection. Texas, Vice President Johnson’s home state, was a problem, for it had 11 electoral votes, and Kennedy’s sudden attention to the civil rights struggles of African Americans damaged his popularity there. Then there was the ongoing and acrimonious struggle among Texas Democrats. The state’s liberal Democratic senator, Ralph Yarborough, and its conservative Democratic governor, John Connally, were feuding, with Vice President Lyndon Johnson caught in the middle. Kennedy wanted it stopped. It was to heal this schism, unite the state’s Democrats behind the administration, and secure Texas’s electoral votes that Kennedy, Johnson, and their wives set out on a goodwill tour of the state the week before Thanksgiving.

The party left Washington on November 21. From the capital it would travel to San Antonio that afternoon, then to Houston. Late on Thursday night, the Kennedys and their entourage would fly to Fort Worth. On Friday morning, the president would speak at a breakfast at their hotel there. Though a motorcade from Fort Worth to Dallas would have been feasible, it certainly would have disrupted the weekday lives of the driving masses, and a Dallas landing in the presidential plane would carry more political weight with Texans anyway. Planners had, therefore, opted to take the short “hop” by air. The plane had barely departed Fort Worth before it was taxiing into Love Field. After a motorcade and a luncheon in Dallas, the party would travel to Austin, the state capital and Governor Connally’s domain, and then, for rest and relaxation, to a gala dinner at the L.B.J. Ranch, Vice President Johnson’s home.

Air Force One touched down in Dallas at 11:38 A.M. on Friday November 22. After greeting the dignitaries present and “working” the large and enthusiastic crowd along the fence, the president and Mrs. Kennedy climbed into the rear seat of SS 100 X, the presidential limousine that had been flown in from Washington. Secret Service Agent William Greer was to drive. Agent Roy Kellerman sat to his right. Governor Connally and his wife Nellie occupied jump seats in front of the Kennedys. The motorcade departed for a drive through Dallas on route to the Trade Mart, where the president would speak at another luncheon.

At 12:29, the motorcade was on Main Street approaching the Stemmons Freeway that would take it to the Trade Mart. The freeway was not accessible from Main Street, however. To reach it, Greer turned right onto Houston Street, traveled only a block, then slowed for a hairpin turn to the left onto Elm Street, into an small park called Dealey Plaza. Immediately after the turn onto Elm, gunfire erupted. Both Kennedy and Connally were hit and severely wounded. Connally collapsed into his wife’s lap. Possibly because of his stiff back brace, Kennedy did not collapse; He was nearly upright when the last shot rang out, striking him in the head and destroying his brain. The limousine sped to Parkland Hospital, just beyond the Trade Mart. There, doctors pronounced John F. Kennedy dead at 1:00 P.M. He was only 46. After emergency surgery for a “sucking” chest wound and wounds to his wrist and thigh, Governor Connally survived.

Shortly after the shooting, someone murdered a Dallas Police officer, J. D. Tippit, at a residential intersection in Dallas’s Oak Cliff neighborhood. Officers who were not occupied with the emergency in Dealey Plaza fanned out looking for Tippit’s assailant. When a young man darted into the Texas Theater without paying, police soon followed. After a brief struggle, they arrested Lee Harvey Oswald, a 24-year-old former Marine who was an avowed Marxist and had once defected to the Soviet Union, before returning to the United States with a Russian wife. The Dallas Police formally accused Oswald of killing Tippit. Later that night, they charged him with the president’s murder. On Sunday morning, November 24, Jack Ruby, a Dallas night club operator with Mob connections, shot Oswald in the basement of Dallas Police headquarters. Shortly after he arrived, by ambulance, at Parkland Memorial Hospital, the accused assassin died in Trauma Room 2, across the hall from the room in which the president had expired barely two days before.

Later in the month, Lyndon Johnson, now president, named a “blue ribbon” commission to investigate Kennedy’s murder. The President’s Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, led by Chief Justice Earl Warren and popularly known as the Warren Commission, released its report in September 1964. It found that Oswald, and Oswald alone, had planned and executed the assassination. He had fired from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository at the corner of Houston and Elm. Ruby, the Commission stated, murdered Oswald on impulse; the two men did not know one another and were not involved in any kind of conspiracy.

The Warren Commission’s findings have sparked controversy ever since it released its report. In the 1970s, a special committee of the House of Representatives investigated the assassination again. The House Select Committee on Assassinations determined that the murder was the result of a conspiracy. While Oswald had fired all of the shots that found their targets, said the Committee, someone else fired another shot that missed. The Committee based this last determination, which touched off a firestorm of rebuttal, on last-minute acoustic examination of a police “dictabelt” recording, supposedly of sounds from the motorcade, including “impulses” it said corresponded to gunshots. The F.B.I. and the National Academy of Sciences quickly debunked the acoustic evidence, finding that the sounds on the dictabelt were transmitted more than a minute after the shooting. Today, the House Select Committee findings are discredited and are almost universally ignored by the media. The original findings of the Warren Commission, that there was no conspiracy in the assassination of John F. Kennedy and that one disaffected young man, Lee Harvey Oswald, murdered the president for reasons all his own, remain the “accepted” account of the event.

Interval from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death to the death of John F. Kennedy:

18 years, 7 months, 10 days

The Longest Respite

Sixty-one years have now passed since the shocking murder of John F. Kennedy. With the sole exception of Richard Nixon, who resigned from the presidency in 1974 and lived for another two decades, the ten presidents who followed Kennedy all successfully completed their terms, and President Biden, the eleventh, is scheduled to complete his in a few weeks. On December 23, 2015, though few took notice, the United States passed a historical milestone. On that day, the time since Kennedy’s death exceeded the 52 year, 1 month interval between the commencement of government under the Constitution and the death of William Henry Harrison, formerly the longest period in our history without a presidential death. To what do we attribute this long respite from a type of national tragedy that most Americans now living have never experienced? Of the eight “lost” presidents, half died of natural causes and half were murdered, so the most obvious answers are improved, more sophisticated security and greatly improved sanitation and healthcare.

Presidential security was almost nonexistent until Lincoln took on a few cavalry guards late in the war. They were only escorts, though. No security accompanied him indoors. When John Wilkes Booth approached to enter the presidential box at Ford’s Theater on April 14, 1865, his chief obstacles were not guards, but a White House messenger, who let him pass, and Lincoln’s unarmed guest, Major Henry Rathbone, who was there to watch the play, not to protect the president. Sixteen years later, when President Garfield strolled into the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station, he was accompanied only by James G. Blaine, his secretary of state. After two successful assassinations, even McKinley had insufficient security in Buffalo in 1901. Not until after McKinley did presidents have something approaching professionalized protection. In the decades since Kennedy, the presidential protection efforts of the United States Secret Service have grown sophisticated indeed. This has surely contributed to the current long period of relative safety for our presidents.

There were near misses, just as there were before Harrison’s time. President Gerald Ford survived two assassination attempts in September 1975. The first was apparently symbolic and posed no real threat; the other could have been deadly. On March 30, 1981, John Hinkley fired six shots at President Ronald Reagan on a Washington street corner. Reagan, who was 70, was struck under his arm by a “flattened” bullet that ricocheted off his armored limousine. The bullet passed close to the president’s heart. Reagan was rushed to the hospital for emergency surgery, rallied, and survived. Coming, as it did, in broad daylight on a bustling city street as they went about their workaday lives, the Reagan shooting was a sort of collective nightmare for the American people: a bitter reminder of November 1963, which suddenly did not seem so long ago. Other less lethal plots and even some thwarted attacks were to follow, but in the six decades since Kennedy’s murder, no American president has come closer to death than Ronald Reagan did in March 1981.

Unsurprisingly, in the public mind, presidential wellbeing now mostly concerns protection from physical attack. With occasional exceptions, since Eisenhower’s time, the question of presidential health has received little attention. Recently, this trend has begun to change. With President Biden now in his eighties and President-Elect Trump preparing to return to the White House at 78, media figures and ordinary Americans now routinely speculate on the health of the president, and of those who hope to be president, as readily as they discuss the injuries of collegiate and professional athletes.

Despite this growing sense of concern, it remains notable that no incumbent president has died of natural causes since Franklin Roosevelt, nearly 80 years ago. Modern medical knowledge and a better understanding of sanitation and infectious diseases are surely the reasons for this. William Henry Harrison’s illness would probably not be considered serious today, and it would be unlikely to kill him. The kind of illness that killed Zachary Taylor is now almost unknown in the developed world and would probably never be a threat to a president. Though it cannot be proved, Taylor’s 1850 gastrointestinal condition was likely caused by the filthy living conditions in the Washington of that era. The White House, in particular, was regarded as a breeding ground for dangerous illnesses. Young Willie Lincoln’s heartbreaking death in 1862 was quite similar to Taylor’s, and modern researchers suspect both may have been sickened by the White House’s primitive water supply. By the time of President Benjamin Harrison (the grandson of William Henry Harrison), in the 1890s, the White House was considered by some so riddled with pestilence that many people wanted it torn down, and Mrs. Harrison made a hobby and a political cause of doing so.

Americans of the modern era cleaned up Washington. They paved the streets. They retired the horses. They installed modern water and sewage systems. They rerouted Tiber Creek, the filthy, stagnant open sewer that once poisoned the atmosphere around the Executive Mansion. They stripped the White House to its outer walls and rebuilt it, banishing the rats that had tormented its occupants for generations. The world has changed. Presidents still get sick from time to time, but they don’t contract typhus or cholera.

Unlike Harrison and Taylor, Harding and Franklin Roosevelt died of chronic illness. Roosevelt, who had top quality healthcare for his time, had been diagnosed with congestive heart failure. Harding, who was cared for by homeopaths and other quacks, probably had it as well. Though Harding’s doctors listed his cause of death as “apoplexy,” modern researchers are certain he died of a heart attack. Both their cases raise interesting questions that may provide clues to a third reason why presidents’ lives seem more secure today. Had Harding not died in the summer of 1923, it is almost certain that he would have been much sicker by the summer of 1924, when the Republican Party would choose a candidate. He probably could have been nominated anyway in that era, but could he today? Roosevelt’s case is more stark. Many insiders knew, in 1944, that he was a dying man. The Democratic Party played this down, did what it could to reassure the voters, and took no extraordinary care in choosing a vice presidential candidate. Could the Franklin Roosevelt of 1944 be nominated for the presidency today? Probably not. The exhausting pace of a modern campaign, relentless media attention, and glaring and brutally candid television exposure would make hiding the truth impossible and would foster public demand for a new candidate, even in the case of the great F.D.R. Clearly, modern media attention acts as a filter of sorts to prevent dying or seriously ill candidates from being nominated, let alone elected. The recent case of President Biden bears this out. Re-nominated by the Democrats, who mostly dismissed concerns about his age, after one disastrous debate performance in which he seemed unfocused and confused, they turned on him and forced him from the race.

One troubling question remains. When Harrison and Taylor died, each was widely mourned. Lincoln’s murder brought a torrent of grief throughout the North and even in parts of the defeated South. Garfield and McKinley were lauded as men of unusual ability and grace who saw themselves as custodians of the national business, and in both cases this view was accurate. Harding and Roosevelt both died far from Washington; grieving Americans lined the railroad tracks day and night to watch their funeral trains pass by. Finally, the tragic blow of Kennedy’s death, painfully familiar, yet somehow unlike anything that had happened before, united Americans, through television, in a shared experience that managed to be at once horrifying and majestic. Could any of this happen today? Maybe. Hopefully. The tenor of recent politics, though, suggests that it might not. Harrison, Taylor, Garfield, McKinley, Harding, Roosevelt, Kennedy—to some degree, in the special context of the Civil War, even Lincoln–were each, in life, the American president. In death, though, each became America’s president. Eventually, sooner or later, our long respite will end. By accident or fate or design, our president will die. Could the Americans of the twenty-first century, as Americans of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries did, find unity in grief for the head of state? If the president of the United States should die today, tomorrow, or next year, how many, and which segments, of the American people would even care?

- This is a blog post written for a popular audience. It is not a scholarly article, though much of part one, concerning William Henry Harrison and John Tyler is based on a scholarly monograph I, myself, wrote. That paper is carefully documented, is available on this blog, and is referenced in footnote 2. I did not document the rest of this article because all of the information in it is either readily available from public sources or could be located with some effort. I wrote nearly all of it from memory based on decades of casual study and consideration, and I do not claim to be breaking new historical ground. As always, I am just trying to entice people, especially young people (like my students, past and present) to love history as much as I do. Direct questions or concerns to kevin_terral_brewer@yahoo.com. ↩︎

- While it is true that George Washington did not take the oath of office until April 30, the new Constitution, by law, became operative on March 4, and the electors had already voted. While most sources indicate that Washington’s presidency “began” on April 30, when he took the oath of office, as a legal and practical matter (though by no means a settled one), it seems accurate to regard him as president beginning on March 4, long before he arrived in New York. He could not have made presidential decisions or otherwise “executed” the office without the formality of the oath, but, despite much public mythology to the contrary, the Constitution does not state that the oath somehow makes one president. The view that Washington’s term began on March 4 is bolstered by the Constitution’s explicit provision for a presidential “term of four years” and by the fact that Washington’s first term ended not on April 30, but on March 4 (some would even argue March 3, but that is a different discussion), 1793. For a more detailed discussion and some source material, see my monograph, “This Most Interesting Moment: Legend, Fact, and Speculation in the Death of William Henry Harrison and the Accession of John Tyler,” footnote 32. Available on this blog. It can be accessed directly at kevinterralbrewer.com/harrison-tyler/. ↩︎

- Much of the Harrison information here is drawn from my more comprehensive monograph, “This Most Interesting Moment: Legend, Fact, and Speculation in the Death of William Henry Harrison and the Accession of John Tyler,” also available on this blog. It can be accessed directly at kevinterralbrewer.com/harrison-tyler/. ↩︎

Pardon me for not reading this with an editing eye🙃. I was too pulled into the narrative. Fascinating. Your speculation about the mindset of the American people today provocative, to say the least.

I am so happy that you liked it.

Kevin,

Needs to be in a historical journal! I predict it would unite for a very short time, but America’s attention span is short, and the many forms of media would help divide us quickly after.

Also, the Garfield story is one of my favorites in teaching U.S. History. So many “what ifs”.