Category Archives: Miscellany

Matthew Perry, “Chandler,” and the Bigger, More Terrible Thing

Last night, Leslie and I sat in our living room chatting with my cousin Steve, who was visiting from Florida. Somehow, the conversation turned to Friends star Matthew Perry. As Leslie can attest, I have been talking a lot about Perry in recent weeks. In September, I decided to move well outside my area of interest and my literary comfort zone to read his 2022 memoir, Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing. I tried to describe to Steve the degree of Perry’s self-confessed addictions and the physical, mental, and emotional damage they have visited upon him. We talked of his 55 Vicodin per day habit, the corrupt people who helped him feed it, and how the opiates caused his colon to “explode,” nearly killing him and leaving him with a temporary colostomy bag. As to whether he was still using, I said that Perry wrote in the book’s closing chapter that he has stopped. I concluded on a pessimistic note, though. I didn’t see how anyone so severely addicted and with all that money could ever quit.

About 15 minutes later, our youngest child Quinn, who is a college student living on campus, sent Leslie a text message that read, “MATTHEW PERRY DEAD!”

I will state up front that I am not holding myself out as an authority on the life and career of Matthew Perry. With the exception of a handful of favorite actors and musicians, my opinions on celebrities and their usually self-imposed torments range from indifference to contempt. Until I picked up his book, my knowledge of Perry’s life and his struggles would have fit in one modest paragraph. To my surprise, I wasn’t twenty pages into this thing before I was thinking to myself, “I must write something about this book. My friends are going to be so surprised when I do.” I finished the memoir about five days ago; its author is now dead, and here I am writing something far different than what I had planned.

Like many people my age and younger, I watched Friends off and on during its original run and have occasionally watched since, though I was never a dedicated fan. I did think the writing was clever and funny and that the principal stars were immensely talented. It was light. It was breezy. The characters were lovable and quirky, and if you watched it just to laugh and relax, you would; I did, anyway. I remember the first time I saw the show. Leslie always watched it. She and I were engaged, and I happened to be at her house when it came on. It was season 2, episode five (yes, I had to look that up): “The One with Five Steaks and an Eggplant,” in which Ross, Monica, and Chandler, all relatively successful in professional careers, are not sensitive to the financial problems of Phoebe, Joey, and Rachel, who are struggling in dead-end jobs. This puts a strain on their friendships: a problem that seems relatable enough.

It is fashionable, today, for people to burnish their images by denouncing Friends: It was trivial. It was a series of one-liners. It was unrealistic. It belabored story arcs. It wasn’t diverse. It was insensitive. None of these is universally true of the show, but each has some validity. It is easy to forget, though, that Friends, like every other entertainment offering, was simply a reflection of its time. The show was nothing less than an entertainment phenomenon during its run, and it did feature, for those who chose to see them, themes that mattered: the angst of modern twenty-somethings trying to find their way in a complex and changing urban landscape; the search for love and acceptance; the post-modern phenomenon, often noted by sociologists, of young adults in the developed world moving beyond their birth families, not to marry and establish their own, but to cling to a new kind of “family” made up of peers: “Friends.” I can attest that Friends is not a generational relic, either. I teach in a high school. Just days ago, I saw a student wearing a T-shirt with the Friends logo, and a student-made poster hanging in the hall features “Central High” in a style obviously meant to mimic the logo of Central Perk, the coffee shop that serves as a gathering place on the show. Nearly twenty years after its final episode, Friends is hip again.

I estimate that I have seen maybe a fourth of the 236 Friends episodes. That’s just a guess. Leslie and I have divergent TV tastes, so now, in the age of streaming, we try to have something serious and something light to enjoy together. A few weeks ago, we decided, for our light fare, to begin streaming Friends. As I watched the smiling, handsome, and seemingly healthy “Chandler” who splashed in a fountain in the opening credits degenerate into the drawn, 130 pound ghost of late season 2, I decided to read Perry’s book.

I was utterly shocked by much of what I read even early in Perry’s story. His parents were numbered among the “beautiful people.” They met when his father, a musician, was performing at a beauty pageant in which his mother, the previous year’s winner, was to crown the new queen. His parents’ marriage ended early on, and little Matthew grew insecure and troubled. His mother became Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau’s press secretary, while his father went to California to pursue his dream of acting, which resulted in his becoming the “Old Spice Man” of advertising fame. Who knew?

Perry was drinking by 14, was in California pursuing his own acting career by about 16, and had some success. Eventually, he was drinking entire bottles of vodka (“the kind with the handle”) in one night and became so hopelessly addicted to opiates that he required more than 50 per day just to function. Along the way, he used his incredible sense of comedic timing, his unique speech cadences, and his undeniable charm to win one of the most coveted acting roles in Hollywood: “Chandler Bing,” in what was then called Friends Like Us.”

In his memoir, Perry outlines how the main cast members were all warned that their lives were about to change forever and how they all became unbelievably rich. His love for his fellow members of the Friends sextet was unconditional to the end. He reveals his unrequited longing for Jennifer Aniston; how Courteney Cox demanded equal billing for all six actors, when she, with her previous sitcom success, might have demanded more than the others; and how David Schwimmer, already well-known in some circles, matched Cox’s selflessness when he insisted that all six actors negotiate for salary as a unit, rather than separately. Schwimmer, Perry asserts, made them all multi-millionaires. Matt LeBlanc, says Perry, was the cast member who had the least to lose and who grew the most on the show. Lisa Kudrow was the funniest person he ever knew.

As I read Big Terrible Thing, I grew more fond of the show and reflected more about the cult of celebrity and what it must have been like for these six young, beautiful, talented, and mostly unknown people to suddenly be caught up in this whirlwind. Perry, and probably all the rest of them, had prayed for fame and fortune, but that could not have prepared them for the magnitude of what came. I found it endearing that they clung to, and fought for, and defended each other. Never was this more the case than when the others had to close ranks to help their friend Matthew Perry, who descended into his personal hell despite (as he regularly points out) the money and the fame he had so craved.

Big Terrible Thing is not a happy book. It is the story of a talented, successful, and very rich young man who, as he implies, would have traded it all to be normal and to be able to live his life without poisoning himself. It has moments that remind the reader how different our ordinary lives are from those of the rich and famous. In one account, Perry is in a wildly expensive drug and alcohol rehabilitation center (one of many in his lifetime) in Switzerland, on the shores of Lake Geneva. The center discharged him with, he thought, an agreement that a California physician with whom they consulted would place him on a maintenance regimen of his favorite opioids. He arrived home to find that the California doctor refused to do so, saying he only had to “consult” with the doctors in Switzerland but did not have to follow their instructions. Perry made a call, put down $170,000 to charter a private jet, and flew back to Switzerland for his drugs that very night.

Not surprisingly, a man living such a life has many opportunities for reflection and to develop bitter hatreds. Perry hated people who said addicts should just “quit.” He hated the “industry” of high-end drug and alcohol rehabilitation facilities that cater to celebrities and the wealthy, considering them opportunistic scams set up to part desperate people from their money. He hated (in no uncertain terms) the manufacturers of colostomy bags because of the poor quality and humiliating failures of their products. Indeed one of the things that finally did induce him to stay clean toward the end was the fear, instilled in him by a brutally honest doctor, that if he required another colostomy it would likely be permanent.

Perry’s years of suffering also left him with sincere loves. He loved his mother and father, despite his rocky relationships with them and the undeniable truth that they often failed him when he was a child. He loved Julia Roberts, one of the most famous and beautiful women in the world, who pursued him when he was only just becoming known and became his girlfriend. He amazed her by breaking it off with her, not because he didn’t want her, but because he was terrified she would desert him. He loved Alcoholics Anonymous because it doesn’t give up on people no matter how many times they fail and because, when he was able, it allowed him to help other addicts. He loved everyone directly connected to Friends. Indeed, there were times when his love for the show and his unwillingness to let down the cast and ruin their lives was the only thing keeping him alive. He loved life. This last seems unlikely, but he said so over and over. He was, at heart, a happy person who lived to make people laugh, something he had been doing almost since he could walk.

At the end of his memoir, Matthew Perry, whom, he had written earlier, you the reader may know by “another name,” professed that he was clean and sober but physically destroyed; covered in scars, both physical and emotional; and quite alone when he might be sitting with any one of a dozen beautiful women watching his children play. Over and over, he said or implied two things: through it all he wanted to live, and money and fame don’t fix you if you’re broken, no matter how ridiculous those without money and fame might find such an assertion.

Matthew Perry, “Chandler Bing,” died last night. He embraced his own troubled life, and he dreaded death, a bigger and even more terrible thing. He drowned in a hot tub at his home. Early reports indicate there were no drugs present. A month ago, I barely would have noticed; now I find myself quite saddened by it all and wishing he could have lived to win back some of what he lost and to help more people. I guess that’s the power of the written word.

Long Shadow Revisited

Five years have passed since I published, on American Path[o]s, “August’s Long Shadow,” a personal memoir of the the events surrounding the 1988 murder of my friend and fraternity brother Thomas Baer (kevinterralbrewer.com/baer/). Looking back, I am struck by the degree to which this one written piece has impacted my conception of who I am and certainly of who I was. My blog is a simple hobby and, admittedly, one on which I expend little energy. With retirement approaching, I daydream that someday it may yet become a going concern, but for now I repost my old research papers and pound out the occasional history-related tale, trying to bring dead presidents and others back to life using essentially the same story telling techniques that have kept me in work and, I am told, successfully so, for nearly three decades. I am content with this.

“August’s Long Shadow” is different, though. I didn’t know it at the time, but it is.

As I have said before, the piece is memoir, not history. When I first began writing, in considerable secrecy, in the spring of 2018, I wasn’t so sure. At the time, I did think someone could, perhaps should, write a history of the case. I had the training to do it, on a modest scale at least, and I had personal connections with many of the principals that would make some of the surely voluminous research easier. All of the research necessary for such an undertaking would not be easy, however, and the prospect of wading through the archives of the Knoxville papers; the Knoxville Police Department; and, God forbid, the University of Tennessee, while working a full-time job and raising children, was daunting, especially when the university, in particular, would have no incentive to cooperate with such a project and might arguably have incentives not to. There were other concerns. A history would have to be nearly perfect, scrupulously documented, and, importantly, could not be written without approaching more distant people, some of whom would surely resent the intrusion. That I was not willing to do. As I, myself, observed in the memoir, we all have uneasy relationships with the scars of August 1988. A memoir would be different. I could simply interview a few good friends who were happy to help; double-check my own recollections (several of which were proved mistaken, requiring revisions in the text) surrounding an event that I, after all, did not personally witness; and consider and then relate in prose how that event impacted my life, the lives of those closest to me, and my beloved fraternity. Self-indulgent, perhaps, but it is a blog, after all. That I, at some level, needed to write such an account never really occurred to me until it was nearly complete.

A few years ago, I sought out and wrote an old friend who was an important part of my life in those long ago days, seeking input on this project and writing, “Too many things happened to me at the same time back then (you too, I think).” I never received a reply; the past does not speak to everyone. I almost envy those it spares, because it never stops speaking to me.

So, I had written a memoir, and to my surprise, I discovered that it peeled away multiple layers of my own young adult life. Every day that I worked on the project, I realized more and more that it was, ultimately, a short, focused autobiography of sorts. It became, in the end, a story not only of a tragedy that ended the life of a friend and disrupted a beautiful part of my young world, but also of how other events—my college graduation (with no family present); my first, troubled days in law school; my brother Tim’s devastating A.L.S. diagnosis (the reason for my lonely graduation); and a new and ill-timed relationship with a much loved girlfriend—intersected that awful, empty event at 1800 Lake Avenue and upset the equilibrium of my happy life.

Of the tragedy itself, I can say that my perspective on it defies the passage of time. I can see and almost feel it all: that dreadful night of phone calls, isolated in my apartment in Memphis, cut off from my suffering and bewildered friends; the melancholy November drive across the state with Ron Powers to visit my emotionally wounded fraternity brothers, my girl, and the scene of the crime, a dim warning from F. Scott Fitzgerald—of all people—fluttering in the recesses of my mind, whispering that what I found there might not be as it was when I left it; a far later visit to the same place to confront the ghosts and to acknowledge that it was, indeed and finally, over. I have heard it said that we write to get to know ourselves. That was my experience in 2018. It wasn’t just introspection, either; a young colleague approached me after reading the memoir and said solemnly, “I feel that I understand you better after reading that.”

“That’s funny,” I thought, “I had the same experience writing it.”

My blog has few readers, and for now, at least, I don’t particularly care, but hardly a week goes by that someone, somewhere in the world doesn’t at least open “August’s Long Shadow.” Over the years, this has led to moving and sometimes chilling exchanges. It has put me in touch with Tom’s sister and, indirectly, his father. Several of Tom’s cousins and other relatives and friends have thanked me for writing about him in a way that illuminated a little of his lovely, quirky nature, and that was touching. Others, total strangers, wrote to chat and to share with me their own memories of August 20, 1988. A woman wrote that she was in the condos across Terrace Avenue on the night of the murder and watched the drama unfold from her window. She was, she said, so traumatized that she left U.T. the next day and never returned. A man named John wrote saying he could supply key information about why the murder occurred. He had been in an altercation with Underwood, the killer, the night before and, since he lived near the Phi Kappa Tau house, speculated that Underwood may have thought he was a member of our fraternity. This explained so much if true, as Tom’s assailant had asked for “John” the first time he entered our house that night. The man said he would contact me in a few days with more information and would consent to an interview. When I did not hear anything, I contacted him. He said he had changed his mind and didn’t want to be involved. Finally, a few years ago, a United States attorney for the Eastern District of Tennessee wrote me seeking contact with the Baer family. The killer, predictably, was in custody again, charged with being a felon in possession of firearms, and the government wanted the Baers to have a say in what would happen next. I passed the information on to Tom’s sister, who has become something of a social media friend, but I didn’t follow up. It had been 33 years; the shadow is long indeed.

Human memory is beautiful, painful, and essential to who and what we are. Unfortunately, it is also something of a blunt tool at times, maybe most of the time, maybe always. Reconnecting, not just with what “happened” (always a tricky proposition in academic history) but with what people felt when it happened, can hone our memories and elevate mere chronicle into something worth chronicling. Some say the more emotion we let creep into our memories the less useful they become in any historical sense. Maybe. But who cares? And do we really want to live without that? As David McCullough, a man who spent his life writing with heart about the past once said, ” No harm’s done to history by making it something that someone would want to read.” In exploring and documenting our own pasts and embracing all the happiness and pain we find there, we can discover all kinds of truths and connections that were hidden just out of sight. What better use could be made of writing? That was my experience in recounting my own memories of the death of Tom Baer—a good young man who did good things, loved everyone without judgment, and inspired love in return—and how it has coursed through so many lives over the decades, including the lives of some who, like me, were not there to witness it but nevertheless found themselves swept up in its wake.

K.T.B.

August 2023

An Open Letter to the People of Big Sandy, Tennessee and to All Friends and Supporters of Big Sandy School

Dear friends,

My earliest memory of Big Sandy School is a scary one.

When Tim, my older brother, was in the first grade, my mother brought all three of us, with Greg just a two-year-old, to the school library for a PTC meeting. Someone had the idea to take all the children who were big enough to the gym to run and play while the adults did Parent-Teacher Conference business. One of the aging, gray-haired ladies with cat-eye glasses who seemed to run everything in that long-ago time agreed to supervise. Greg stayed behind, of course, but Tim and I joined in with some other kids and went into that vast, cavernous space with the devil’s face painted in the middle of the floor. I was four and had almost never been away from my mother, except with relatives, and I was not a fan of the devil’s face (no cartoon devil he), so I protested—loudly. Concluding that I was too young to participate without being a pain, the old lady sent me back. Someone escorted me into the door of the school building and left me there. The hall lights were not even on. All good mothers can recognize their children’s shrieks, and no one had a better mother than I did, so my shrieks came loudly and clearly, and Mom came running. I was none the worse for wear, but I do remember it, and Mom told that story with a flash of anger for the next fifty years.

That was in 1969.

I suppose Big Sandy School has always been a part of me.

I was a student at Big Sandy from 1971 until I graduated in 1983. Believe me, it was no part of my plan to return. I loved living in Knoxville, and I wanted to be a lawyer, but like the protagonist in Mr. Holland’s Opus (or like Gabe Kotter, if you prefer a less ostentatious simile) I felt at times that fate was conspiring behind the scenes not just to push me into a classroom, but to push me back to my old school. My brother Tim’s long struggle with Lou Gehrig’s disease, my discovery that I did not like the law nearly as much as I liked the history of the law, and changes in my own life led to a teaching license in 1990 and, in the fall of 1995, to Big Sandy School. I didn’t seek the job; it sought me. I didn’t even apply for it. Sometimes the world works that way.

For the first three years I was a teacher at Big Sandy, I did not even have a classroom. Many of you remember what it was like there in those days, with K-12 in one building: halls so crowded between classes that you could barely move; courses meeting in dressing rooms, storage rooms, and abandoned bathrooms; teachers having to vacate their rooms during planning time so someone else could teach there. In the fall of 1998, the new high school building opened. I found my new quarters, unfurled my maps, grabbed a cup of coffee, and room 208 at the end of the hall became the nerve center of history education on the north end of Benton County.

Now, 28 years after I returned, the halls aren’t crowded anymore, there are rooms to spare, and I have been teaching two classes per day in Camden since August. Whatever accidents or designs of fate led me, all those years ago, back to where I started and into room 208, where no one else has ever taught, have changed course. On May 19, I will teach my last class at Big Sandy. Next year, along with the high school student body, I will be relocating full time to Camden Central High. I knew this day was coming, but I have heard people talk about it since the 1970s, and when you hear something discussed for that long it becomes difficult to think of it as real.

I have long cast nervous glances at the changing landscape of my workplace, with so many old friends and mentors gone and so much energy lost, and wondered how it would all turn out. In my personal daydream, Big Sandy High’s last day always came on my last day as a teacher. I would make a General MacArthur-like valedictory address to the masses, bask in their applause and adulation, and the school and I would fade away together. It wasn’t to be, though. It’s too soon to retire, and now I face a difficult task, a task complicated by my age, of which I am increasingly aware. I have to transplant what I hope was a worthwhile career, one that touched people’s hearts and minds, into a new and bigger place where the magic—and at times it did feel like magic—may not work. If the magic fails, it will not be the fault of the people of Camden Central High School, where I have good friends, some of whom were once colleagues at Big Sandy. The people there have welcomed me with warmth and support, and the administrators of both the school and the district have done everything in their power to smooth this transition.

Twenty-eight years ago, I was at the bottom of my own school’s seniority list; today I am number 25 for the entire district. For all those years moving up the list, I am indebted to many people associated with Big Sandy School, but for fear of leaving someone out I am going to name only one. It was Mrs. Diane Padgett who reached out to me and offered me this job; she always, always believed I had “it,” whatever “it” is, and she was happy to have me back. That was a life-changing phone call, and I am eternally grateful to her.

I will not lie; it is going to be painful to walk out of BSHS. I have probably spent more time in my Big Sandy School classroom than in any home I have ever lived in, and I suspect I have spent more of my life on the school’s few acres of land than in any other place. I am ambivalent as to whether that denotes success or failure on my part. I have been able to impact a lot of lives there, and I do hope that most of those people believe they have benefited from my efforts. There have been many times when I reflected that I once had “bigger” dreams, but then I look around and see people with “bigger” lives who have little to feel good about at the end of the week. I never had that problem. My work at our little school was difficult, frustrating, and sometimes infuriating, but it was work that mattered, and that, my friends, is priceless.

So, thank you, Big Sandy, for your tireless support of my efforts to teach at your—our—school. When you pause to think of it, it is quite something to have people entrust their children to you, day after day, for so many years. It was a real honor, and I learned at least as much from the students as they learned from me.

To the surprise of no one, I will close with an anecdote from history. In February 1861, with the country going to pieces, president-elect Abraham Lincoln left his adopted hometown of Springfield, Illinois to travel to the nation’s capital, “not knowing when or whether ever” he would return (he did not). He left to me a better closing line for my career at Big Sandy than I could ever write for myself:

“My friends, no one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything.”

K.T.B

May 2023

I had a Teacher: A Tribute to Mary Lou Marks on her Retirement

I originally published this tribute in 2017 as a “note” on Facebook. Facebook no longer supports notes and has even deleted them. I narrowly managed to save this one and am publishing it here on my blog for safekeeping. Mrs. Marks has since unretired and re-retired. No matter what she does, this tribute is from the heart and will stay the same.

One Thursday night, 34 years ago this month, I stood capped and gowned in a graduation reception line at my high school. Among those who came by to congratulate my classmates and me was our English teacher for the 8th, 9th, 11th, and 12th grades. In her polished (read: non-country) delivery, she posed an unexpected question: “Mr. Brewer,” she began, employing a formality to which I was little accustomed, “have you ever seen The Graduate?”

I had not.

She quickly explained that in the graduation party scene at the beginning of the famous 1967 film, Mr. McGuire, a business executive of some kind, takes young Benjamin Broddock aside and gives him one cryptic word of advice for his future: “plastics.”

“My word to you, Kevin,” she continued, “is nonfiction.”

This woman, whom I had known for years, had admired, and had sometimes feared, went on to say, with the same candor she might use if addressing an adult peer, that I had talent, that I had gifts, that I had something to contribute. Even as an unsophisticated 18-year-old from a microscopic town, I had the discernment to realize that, in this hurried exchange in a sweltering cafeteria, I had received a special dispensation from someone whose opinion mattered—someone who did not trade in idle flattery on special occasions, or on any occasion.

I first became aware of Mary Lou Marks as a young child. She was the “big kids’” English teacher who, each morning as I waited for the bus, passed my house in a brown Ford Pinto. She seemed intimidating, and the buzz was that she was “different.” I was not optimistic; there were few greater sins than being “different” in 1970s Benton County. I, for one, wanted no part of it.

It was not until I appeared in her class for eighth grade English, in the fall of 1978, that I came to know her personally. My friends and I did not know what to make of her. It was true: she was not like us. We were as country as turnip greens; she, decidedly, was not. It was clear she was from the North, but she wasn’t a Yankee of the “aunt so-and-so moved up north during the war” school. I knew many of those kinds of Yankees and Yankee poseurs. They were from Akron or Detroit or Cleveland and spent much of their time there making money and pretending they were not from here, before retiring to move back here to live on the cheap among the common rabble. This was different. Her dialect was unfamiliar, rich and precise, and while she made it look easy, it always seemed as though she had chosen each word with great care. When she spoke, it seemed I was not merely hearing the words, but hearing the years of thought, education, and experience that had cultivated the words. I soon pieced together the essential facts of the story: this woman was an honest-to-God New Englander—perhaps the first I ever knew—and more than that, she was an intellectual. She was from Connecticut, for God’s sake! Were people from Connecticut? For her, New York was a real place to which one might dash for a little Christmas shopping. To us, it was dimly remembered scenes from Family Affair, or, more recently, the credits for All in the Family.

She was not like us.

With some exceptions, there are few more rude and worrisome creatures than middle-school age boys. This interloper with the careful diction, the big vocabulary, and the love of poetry wasn’t going to push us around! I languidly joined in the resistance, but my heart wasn’t in it. My parents did not tolerate bad behavior if they knew about it, and, in truth, I was different too. While my friends were hunting or fishing or raising hell with older kids, I was sitting at home building models, pondering time travel, and reading the World Book Encyclopedia. I had a college undergraduate’s knowledge of US presidential history by age 10 and a college graduate’s knowledge of it by age 14. I wrote stories. I loved words. My curiosity knew no bounds. In time, I began to make common cause with this scholarly young English teacher.

And we worked. Perhaps the most shocking thing about Mrs. Marks’ class was that we were not just always occupied but were always occupied with something that mattered. This was a revelation. Once per week, we learned ten new vocabulary words. I can still remember some of them—can in fact still see her writing them on the board in that old firetrap classroom with the giant, wavy glass window. What words they were! Macabre, limn, complement (not compliment!), vapid, esoteric. Mrs. Marks would write the phonetic spelling, complete with the vowel signs, first, and we would try to pronounce them before we saw the actual spelling. This was one of my favorite activities. I found I was quite good at it, and, to my delight, she thought so too.

The years went by. Mrs. Marks was my English teacher for both the 8th and 9th grades. She took off the 1980-1981 school year to have a child. I was not amused, but I was glad to see her back for my junior year. By then, I was confident, enthusiastic, and a devourer of books. There seemed to be a special level of understanding between us. When she instructed the class to choose a major work for our junior book report, I came to her with John Steinbeck’s East of Eden. I knew of Steinbeck, but I knew nothing about the book, and she seemed concerned. After giving it some thought, she said she was going to let me report on it. East of Eden was “mature,” she said, adding, “I probably would not let any other student do it, but I’ll let you do it.” Flattered, I threw myself into this painful novel, with its tortured psyches; its notorious, fetishistic brothels; and its deeply flawed characters. As I read, and as the story became more troubling, I sensed the trust that Mrs. Marks had reposed in me with this assignment, and the risks she was taking. When the time came to write my report, I dispensed with euphemisms, boldly incorporating the word whorehouse into my text. I felt that I was taking a chance using such an offensive term in a book report for a female teacher (or any teacher), but she trusted me, so I trusted her. She never said a word about it. She treated that daring word as though she had run across it in The New Yorker, rather than in a high school junior’s book report. More than three decades later, I can still recall how it felt to be treated that way—like an adult, maybe even a budding intellectual.

In my senior year, we did more writing, more reading, and more speaking. The latter has served me well. Here, too, I took chances because Mrs. Marks allowed it. For my spoken piece, which I was to annotate for emphasis, breathing, and inflection, I chose the ghastly shooting scene from William Manchester’s The Death of a President:

The Lincoln continues to slow down. Its interior is a place of horror. The last bullet has torn through John Kennedy’s cerebellum, the lower part of his brain. Leaning toward her husband Jacqueline Kennedy has seen a serrated piece of his skull—flesh-colored; not white—detach itself. At first there is no blood. And then, in the very next instant, there is nothing but blood . . .

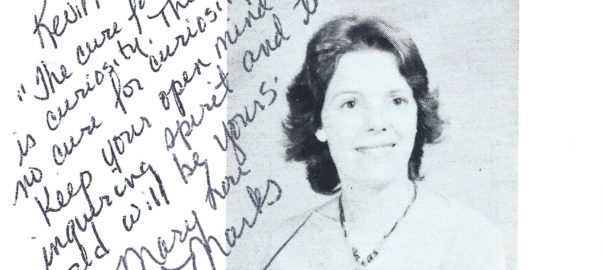

Today, it is easy to imagine a teacher rejecting a request to work with such material. Mrs. Marks knew it mattered to me, so she allowed it. I guess that is why I still remember it so clearly. In retrospect, I can see that her test for such things was good faith. Anything worthwhile that you wanted, in good faith, to do, she encouraged. Accordingly, that spring, she signed my final yearbook:

Kevin-

‘The cure for boredom is curiosity.

There is no cure for curiosity.’

Keep your open mind and

inquiring spirit and the

world will be yours.

Mary Lou Marks

As my final year of high school drew to its close, I knew I was well-prepared for the verbal and literary challenges of college, and I knew it was time for a change. I was ready. I guess Mrs. Marks felt the need for a change too. I was not surprised to learn that my last day as a student at Big Sandy School was to be her last there as a teacher. As I went away to college, she was settling into her new position as the librarian and media specialist at Camden Central High. She has been there ever since, compiling material, transitioning to electronic media, and—unsurprisingly—running writing workshops for the students there.

I never became the great writer, but I write still—nonfiction, mostly—and I did become a teacher. Though not at the same school, Mrs. Marks and I have now been colleagues in the Benton County school system for 22 years. During that time, we have had many opportunities to share ideas, written passages, and social criticism; Facebook has made this easier still. Now, at long last, she has decided to retire. I know what she will do: she will travel, and raise her flowers, and visit museums and art exhibits, and watch her grandchildren grow up. And she will read, and read, and read. Behind her, she will leave several generations of men and women from a pair of small towns who will never forget what she gave to them: eyes and ears attuned to words; the ability to connect the imaginary to the concrete; the capacity to gaze across time and space through a book or a story or a poem and to feel the still-beating hearts of writers long dead.

I hope the people of Benton County know how fortunate they have been to have, in their schools, this cultured, literate teacher, who has given selflessly to them, their children, and probably their grandchildren, for nearly four decades. A few years back, Mrs. Marks commented about my vocabulary and my love of history and words. I replied to her the only way I felt I could. I said simply, “I had a teacher who cared about words and beauty and culture and taught me to do the same.”

I know that in this I am not alone.

Well done, Mrs. Marks.

Well done.

Ten-Dollar Bills and Letters of Congratulation: The Unlikely Journey of the Sick Chicken Case

I originally wrote this as a seminar paper for a graduate level American history class at Murray State Univeristy in 2004. I presented it at the annual Phi Alpha Theta conference, held in conjunction with the American Historical Association conference, in Philadelphia in 2006. I am now publishing it to American Pathos.

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt took the oath of office as president, on a rainy March 4, 1933, and dramatically declared to a desperate public that the only thing it had to fear was “fear itself,” few could have imagined that a major cornerstone of Roosevelt’s economic plans would, or could, fall victim to legal arguments involving, in part, the manner in which chickens could be pulled from a coop. That is what happened two years later, however, when four brothers, Joseph, Alex, Martin, and Aaron Schechter, businessmen from one of the grittiest and most notoriously corrupt enterprises in New York, the “live poultry” trade, were indicted, tried, and convicted of violating codes established under Roosevelt’s National Industrial Recovery Act. The United States Supreme Court case that eventually resulted, A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corporation v. United States, was a stunning victory for the Schechters and for opponents of the New Deal. In one fell swoop, it invalidated the National Industrial Recovery Act, the hundreds of codes that had been fashioned in response to it, and the entire regulatory philosophy upon which it rested. The decision is regularly blamed—or credited—with undermining the major thrust of the New Deal and for spurring Roosevelt, in 1937, to pursue his costly “Court-Packing” initiative. Continue reading Ten-Dollar Bills and Letters of Congratulation: The Unlikely Journey of the Sick Chicken Case

Your Guide to the Twenty-Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution

I published this as a Facebook note in 2017, when impeachment and related topics were in the air. That was early in the Trump administration and before anyone had ever heard of covid-19. Now, a few people are asking me about the Twenty-Fifth Amendment again, so I have decided to post it to my blog (Facebook is discontinuing “notes”) and republish.

With President Trump’s various difficulties and the realization that removing a president of the United States from office through impeachment is both difficult and unprecedented, there has been a flurry of discussion about the Twenty-Fifth Amendment to the Constitution.

Several people have asked me about the particulars of this amendment, so here I will attempt to explain it in plain language the way I would explain it to students.

Serious discussion about what became the Twenty-Fifth Amendment began after President Eisenhower’s three major illnesses, one of them a heart attack, in the 1950s. When the aging Eisenhower left the office to a man in his forties, in 1961, interest in the topic died away somewhat, though not completely. After the Kennedy assassination, Congress and the executive branch had to confront a troubling question: what if Kennedy had survived his massive head wound? Already, the country had endured several instances of serious presidential disability, most notably President Garfield’s 80 day decline after his shooting in 1881, President Wilson’s 1919 stroke and its 18-month aftermath, and President Eisenhower’s illnesses. The original constitutional provisions for presidential disability were inadequate and ambiguous, leaving it unclear whether or how the vice president was to intervene. Accordingly, Vice President Arthur refused to do anything at all as Garfield lay dying, and Vice President Marshall followed suit while Wilson was ill. Vice President Nixon met with Eisenhower’s cabinet during the latter’s illnesses and was widely praised for his low-key but effective efforts. In the dangerous Cold War period, though, it was clear that some kind of formal arrangement was necessary, one that would settle all questions of presidential succession and disability.

In 1965, Congress proposed the Twenty-Fifth Amendment. In 1967, the 38th state legislature ratified the amendment, and it became part of the Constitution.

The Twenty-Fifth Amendment has four sections: The first section simply states that if the president dies, resigns, or is removed from office, the vice president becomes president. This was what had been done since the first presidential vacancy in 1841, but the Constitution was actually ambiguous as to whether the vice president was to become president or was somehow to merely act as president. This section settled the question once and for all. It is assumed that it also settled the question of the presidential oath. It is now clear that the vice president becomes president instantly if there is no president; the oath is not an impediment to his carrying out his duties, though a new president would presumably take the oath anyway, for appearances’ sake, as soon as he could do so. Presumably, the congressional framers of the amendment wanted no repeats of November 22, 1963, when an ostensibly leaderless nation lived in danger for two hours while people chased down the presidential oath and a federal judge.

The second section provided a means of filling a vacancy in the vice presidency. Throughout history, there had been 16 such vacancies (there have been 18 to the current date). Eight vice presidents had acceded to the presidency, leaving the vice presidency vacant, seven others had died while vice president, and one had resigned. In total, about 40 years had passed with no vice president—about 22% of the period since the beginning of the American presidency.

After the ratification of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, the president of the United States was empowered to appoint a new vice president whenever that office was vacant; the appointment would require the approval of both houses of Congress. This was the procedure President Nixon used to appoint Vice President Ford in 1973, after the resignation of Vice President Agnew. When Ford became president the following year, he used the same procedure to appoint Vice President Rockefeller.

The third section of the amendment provides a way for the president of the United States to declare, of his own volition, that he is temporarily unable to fulfill the duties of his office. Though the amendment does not specify, this section is understood to address cases of incapacitating but presumably temporary illness of which the president, himself, is aware; surgery; or some kind of family trauma (the loss of a spouse or a child, for instance) requiring that the president have time to grieve and recover emotionally.

The procedures for activating Section 3 of the amendment are specific and relatively straightforward. If the president decides that he is, or will be, temporarily unable to perform his duties, he signs two identical letters to that effect, and “transmits” one to the speaker of the House of Representatives and one to the president pro tempore of the Senate. At that moment, all the president’s powers are transferred to the vice president of the United States, who becomes acting president of the United States. This arrangement remains in place until the now powerless president sends new letters to the speaker of the House and the president pro tempore of the Senate, declaring his inability over, at which time he resumes the powers of the presidency.

The first person ever to serve as acting president of the United States, pursuant to Section 3 of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, was George H. W. Bush. He was acting president for several hours during President Ronald Reagan’s colon cancer surgery in 1985. Vice President Dick Cheney served twice as acting president, for a few hours each time, during minor surgical procedures performed on President George W. Bush.

The provision of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment that is currently generating discussion is Section 4, which provides a way for other officials to declare the president of the United States unable to perform his duties. Section 4 anticipates a situation in which an unconscious or severely physically (or perhaps mentally) compromised president is unable to recognize his incapacity and/or unable to carry out the procedures outlined in Section 3.

Section 4 empowers the vice president and a majority of the “principle heads of the executive departments” (the Cabinet members), or some other group of people that Congress might appoint for such a purpose, to transmit to the speaker of the House of Representatives and the president pro tempore of the Senate, letters declaring that the president is unable to perform the duties of his office. In such an event, the president’s powers would immediately devolve on the vice president, who would become acting president of the United States, just as outlined in Section 3. The president would remain in his position but would be shorn of his powers.

The writers of Section 4 anticipated the obvious: that such a procedure might be used for nefarious purposes, and that the president of the United States might challenge the loss of his powers. The section states that the president can easily regain his powers by simply challenging their transfer, and waiting. To do so, the president need only sign letters to the speaker of the House and the president pro tempore of the Senate, stating “that no inability exists.” After a waiting period of four days, during which the vice president continues as acting president, if no further action is taken by the vice president and the Cabinet (or the vice president and the oft-cited “other body”), the president regains his powers.

When the president signs and transmits the letters declaring that he is not disabled, the vice president and the cabinet (or Congress’s “other body” if it has created one) would have a complex choice to make. They would have to decide whether to “go to the wall” in their insistence that the president is unable to perform his duties. From the time of the president’s challenge to their actions, they would have four days in which to sign yet another pair of letters to the speaker and the president pro tempore, insisting that the president, contrary to his claims, is, indeed, unable to perform the duties of his office. At that point, the dispute would move to Congress.

Section 4 states that if the vice president and his allies challenge the president’s resumption of his powers, Congress is to assemble within 48 hours if it is not already in session, to resolve the question—obviously a grave constitutional crisis. Congress has up to 21 days, during which the vice president will continue as acting president, to determine, by a two-thirds vote of both houses, that the president is unable to perform his duties. If they so decide within the 21 days, the vice president will continue to act as president for an indefinite period (the remainder of the term, or perhaps until Congress agrees with the president in some future challenge—the amendment is unclear). If Congress does not affirmatively declare (by a two-thirds vote of both houses), within 21 day of the president’s adversaries’ written rebuttal to his counterclaim, that the president is, indeed, unable to perform the duties of his office, then the president shall resume his powers.

Discussion of Section 4:

- In the current hyper-partisan context, note that the impeachment process (which is for instances of presidential criminality) requires a simple majority of the House for impeachment and a two-thirds vote of the Senate for conviction and removal. The Twenty-Fifth Amendment’s Section 4 provisions to strip the president of his powers but not his office, on the other hand, require, in their final phases, two-thirds majority votes in both houses, if the transfer of the president’s powers to the vice president is to be made permanent or even semi-permanent. Therefore, if the ultimate goal is the cynical one of simply depriving Donald Trump of power—getting him out of the way—the notoriously difficult impeachment route is effectively easier than the Twenty-Fifth Amendment route.

- Unlike the vice president, who cannot be fired by the president or anyone, the cabinet members serve at the pleasure of the president. Therefore, any collusion between them and the vice president would have to be planned in extreme secrecy, or they could easily be purged by the president before it comes to fruition.

- In the final analysis, the Section 4 provisions of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, though complex and disruptive if carried to their legal extremes, ultimately favor the word of the duly-installed president of the United States over that of the people trying to strip him of his powers. Any attempt to invoke these provisions simply to “get rid” of an unpopular president would probably be met with enough cold feet in Congress to cause it to fail, given the historical difficulty of achieving two-thirds majorities in both houses.

- Though there is obviously no precedent for such a thing, it is always possible that the federal courts could intervene to stop or reverse any perceived “misuse” of the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, or even of the Constitution’s impeachment provisions. This is speculation, of course, but neither procedure was intended to remove or impede a merely controversial or unpopular president. While the courts might invoke the Political Question Doctrine, in effect saying it is none of the judicial branch’s business how Congress deals with President Trump, there is at least a theoretical possibility that the judges could seek to protect the Constitution by halting or reversing Congress’s actions. There is simply no way to know how it might go.

As always, the ancient Chinese curse seems relevant: May you live in interesting times.

On the Impending Public Release of the Warren G. Harding-Carrie Phillips Love Letters

I originally published this piece as a Facebook “note” in 2014. Facebook is discontinuing notes, so I am now moving it to American Pathos.

On Tuesday, the Library of Congress will release, to considerable fanfare, one of the most contested, yet somehow least known, presidential document collections in American history: the long-suppressed love letters of Warren G. Harding to his mistress, Carrie Phillips.

The letters have a complex history.

Jim and Carrie (Fulton) Phillips were neighbors of Warren and Florence Harding’s in the first decade of the twentieth century. The two couples became friends, even touring Europe together. In 1904, the Phillipses’ young son died. Warren had never particularly loved Florence, who was older than he, sickly, and something of a scold, and in the emotional aftermath of the child’s death he and Carrie fell in love. For several years, the friendship between the two couples continued, but eventually Florence caught on and shut Carrie out of her life. Warren, though, was an increasingly busy and important man, first in Ohio politics and then nationally, and he was always on the road, so the affair continued and deepened.

In the early 1910s, the Phillipses traveled to Germany, which was at the height of its power and glory. Carrie fell in love, to the point of obsession, with all things German and remained there for some time. Meanwhile, Warren was elected to the United States Senate from Ohio. Carrie returned to America, but her new love of German culture, and Warren’s position in the Senate, set the two up for a clash when World War I broke out in the summer of 1914. The United States struggled to remain neutral, but U.S.-German relations deteriorated quickly after mid-1915. Warren continued to pour out his heart to Carrie, but his passionate letters were tinged with near-panic as Carrie refused to moderate her outspoken pro-German sentiments. She even began to openly threaten Warren should he vote for a war declaration against her adopted homeland.

In April 1917, the United States declared war against Germany, and Warren, who voted for the war, soon realized that the Wilson administration’s intelligence agencies were investigating Carrie. Worse, there was much to investigate. Carrie and Jim’s daughter was openly courting the cousin of a German heiress who was a known spy. Federal agents arrested the heiress in a Chattanooga hotel room while she was plying her feminine charms to extract troop movement information from a young American soldier stationed at Fort Oglethorpe.

Despite all of this, Warren, and even Carrie, somehow stayed out of trouble, and they continued to see one another at times, but Carrie never recovered, emotionally, from Germany’s loss in the war. For the first weeks after the Armistice, most people assumed that former president Theodore Roosevelt would be the Republican nominee in 1920. Roosevelt died suddenly in January 1919, however, and Warren’s star began to rise in what was certain to be a Republican campaign cycle. Carrie did not want Warren to be president, and it is at that point that the letters begin to suggest that Carrie was blackmailing Warren. In 1920, the Phillipses took a tour around the world, allegedly financed by the Republican National Committee (there is some dispute on this point), and Warren was elected president in a popular and electoral landslide over James M. Cox.

There is little evidence of correspondence between Warren and Carrie after Harding assumed the presidency in March 1921. He died suddenly only two and a half years later. Carrie remained in Marion, Ohio, but became estranged from Jim, who took to the bottle. She was again investigated for disloyalty during World War II. By the mid 1950s Carrie was an eccentric recluse. Her home fell into disrepair and her dogs—German shepherds—were poorly cared for. Eventually she was placed in a retirement home. The lawyer in charge of her estate, Don Williamson, found a sealed closet, and in it a box of letters, nearly a thousand pages, from Warren G. Harding. The letters were scattered, disjointed, undated, and thus wildly confusing. They were also shot through with florid expressions of love, and some were sexually explicit.

For several years, rumors circulated around town that Williamson had the letters. By 1963, the Harding Memorial Association, a group of local relatives and notables in Marion, was preparing for the late president’s 1965 centennial. In conjunction with this, the Association was planning a 1964 transfer of all of its Harding documents to the Ohio Historical Society. In the midst of this, Francis Russell of Massachusetts, a writer, one of several who were planning anniversary biographies of the much-maligned Harding, arrived in Marion. In an old book about the 1920s, Russell had read that during the 1920 Harding campaign all the store fronts in Marion were decorated—all, that is, except the store owned by Jim Phillips. Russell wondered why and soon found out about the Phillips affair and the rumor that Williamson had the letters. Russell tracked Williamson down and saw the documents himself, and that is when the great legal drama began. Russell convinced Williamson to transfer the letters to the Ohio Historical Society. Williamson agreed, and the cat was out of the bag. This set up a fight between Kenneth Duckett, an archivist at OHS, who genuinely wanted to preserve the letters for history; the OHS itself, which, as it turned out (or so Russell alleged) was something of a political arm of the Ohio Republican Party rather than a traditional historical depository; the Harding heirs, who wanted to suppress or destroy the letters; Russell, who wanted to be the first to use them; and American Heritage, to which Russell was a contributor.

Eventually, an easily manipulated state judge, relying on a highly questionable interpretation of copyright law, transferred the letters to the Harding Memorial Association. Duckett, however, had already made several microfilm copies, once actually having a fistfight at the copier when an OHS official tried to stop him, and had secreted the copies at various places around the country. Russell managed to get a a copy to American Heritage, but a court order forbade anyone to use the letters for any reason. Russell became so frustrated that, in 1968, he published his biography, The Shadow of Blooming Grove: Warren G. Harding in his Times, with long rows of hyphens replacing the alphabet characters of the Harding letters. In the end, a later court protected the letters by transferring them to the Library of Congress, where they were to remain under seal until July 2014, fifty years after the controversy began.

And here we are.

Despite many efforts at suppression and delay, the letters were not completely sealed. Russell had made notes in 1963, and a few stray but incomplete copies remained. In 2009, Cleveland attorney James Robenalt, whom I met first in 2011 and again last week, published The Harding Affair: Love and Espionage During the Great War, the only real study ever done of the incomplete letters. Robenalt believes, and I agree, that the letters, contrary to the long assessment of historians, show a Harding who was intelligent, hard-working, engaged, and scrupulously patriotic. Robenalt is calling for a professional reassessment of Harding and his place in history, and I support that effort. That is why I am now associated with the Warren G. Harding Symposium in Marion, and why I have traveled to that event three out of the last four years.

If you find this topic interesting, I urge you to pay attention to the news out of the Library of Congress on Tuesday. However, I would not expect too much in the way of serious treatment of the letters. The media will focus on sex and pet names and the like, and there will be little real analysis. Current politics will also come into play, as there has always been a Progressive political bias among professional historians against the three Republican presidents who served between Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt.

You may want to read Robenalt’s book, The Harding Affair: Love and Espionage During the Great War, which is readily available. You can also consult Robenalt’s web site, www.thehardingaffair.com [2020 note: the link is now dead]. Next year will be the 150th anniversary of Harding’s birth, so that, in conjunction with the release of the letters, will probably lead to a spate of new books.

As for me, you know that I live for this kind of thing, so I welcome any discussion of it on Facebook. Thanks for listening.

—Kevin Brewer, July 27, 2014

Understanding the New Amelia Earhart “Evidence”

Continue reading Understanding the New Amelia Earhart “Evidence”

Marion Eugene “Skeeter” Mallette: In Memoriam

My parents were strict.

During my early teen years, I went places with my older brother, who could drive, or—rarely—with a cousin or family friend. If I wanted to do anything with my peers, though, it had to be school-related, which explains why I spent so much time at basketball games and other school events. They were my social outlet.

The first instance I can recall of getting into a car driven by one my own friends and going anywhere without adults was when I was 15, in the hot, drought-scorched summer of 1980, when Marion Eugene “Skeeter” Mallette pulled his pampered and souped-up Chevy Chevelle into my drive, to take me not to some happy, parent-free event, but to the funeral of our classmate, Chris Bollen. On July 4, Chris had fallen out of a boat on Kentucky Lake (boating with friends was exactly the kind of thing you would never have found me doing at 15) and was struck by the propeller. It was days before searchers found her. Neither Skeeter nor I was particularly close to Chris. She was lovely, and had blue eyes of the sort that are now Photo Shopped onto makeup ads, so, even though we shared a table in one class, I doubt she could have called me by name (Skeeter she would know). Still, her death traumatized my friends and me, the first loss of its kind we experienced. Only with reluctance did my dad consent to let me attend the funeral with my good friend, whom he viewed with some suspicion.

Continue reading Marion Eugene “Skeeter” Mallette: In Memoriam