I originally published this tribute in 2017 as a “note” on Facebook. Facebook no longer supports notes and has even deleted them. I narrowly managed to save this one and am publishing it here on my blog for safekeeping. Mrs. Marks has since unretired and re-retired. No matter what she does, this tribute is from the heart and will stay the same.

One Thursday night, 34 years ago this month, I stood capped and gowned in a graduation reception line at my high school. Among those who came by to congratulate my classmates and me was our English teacher for the 8th, 9th, 11th, and 12th grades. In her polished (read: non-country) delivery, she posed an unexpected question: “Mr. Brewer,” she began, employing a formality to which I was little accustomed, “have you ever seen The Graduate?”

I had not.

She quickly explained that in the graduation party scene at the beginning of the famous 1967 film, Mr. McGuire, a business executive of some kind, takes young Benjamin Broddock aside and gives him one cryptic word of advice for his future: “plastics.”

“My word to you, Kevin,” she continued, “is nonfiction.”

This woman, whom I had known for years, had admired, and had sometimes feared, went on to say, with the same candor she might use if addressing an adult peer, that I had talent, that I had gifts, that I had something to contribute. Even as an unsophisticated 18-year-old from a microscopic town, I had the discernment to realize that, in this hurried exchange in a sweltering cafeteria, I had received a special dispensation from someone whose opinion mattered—someone who did not trade in idle flattery on special occasions, or on any occasion.

I first became aware of Mary Lou Marks as a young child. She was the “big kids’” English teacher who, each morning as I waited for the bus, passed my house in a brown Ford Pinto. She seemed intimidating, and the buzz was that she was “different.” I was not optimistic; there were few greater sins than being “different” in 1970s Benton County. I, for one, wanted no part of it.

It was not until I appeared in her class for eighth grade English, in the fall of 1978, that I came to know her personally. My friends and I did not know what to make of her. It was true: she was not like us. We were as country as turnip greens; she, decidedly, was not. It was clear she was from the North, but she wasn’t a Yankee of the “aunt so-and-so moved up north during the war” school. I knew many of those kinds of Yankees and Yankee poseurs. They were from Akron or Detroit or Cleveland and spent much of their time there making money and pretending they were not from here, before retiring to move back here to live on the cheap among the common rabble. This was different. Her dialect was unfamiliar, rich and precise, and while she made it look easy, it always seemed as though she had chosen each word with great care. When she spoke, it seemed I was not merely hearing the words, but hearing the years of thought, education, and experience that had cultivated the words. I soon pieced together the essential facts of the story: this woman was an honest-to-God New Englander—perhaps the first I ever knew—and more than that, she was an intellectual. She was from Connecticut, for God’s sake! Were people from Connecticut? For her, New York was a real place to which one might dash for a little Christmas shopping. To us, it was dimly remembered scenes from Family Affair, or, more recently, the credits for All in the Family.

She was not like us.

With some exceptions, there are few more rude and worrisome creatures than middle-school age boys. This interloper with the careful diction, the big vocabulary, and the love of poetry wasn’t going to push us around! I languidly joined in the resistance, but my heart wasn’t in it. My parents did not tolerate bad behavior if they knew about it, and, in truth, I was different too. While my friends were hunting or fishing or raising hell with older kids, I was sitting at home building models, pondering time travel, and reading the World Book Encyclopedia. I had a college undergraduate’s knowledge of US presidential history by age 10 and a college graduate’s knowledge of it by age 14. I wrote stories. I loved words. My curiosity knew no bounds. In time, I began to make common cause with this scholarly young English teacher.

And we worked. Perhaps the most shocking thing about Mrs. Marks’ class was that we were not just always occupied but were always occupied with something that mattered. This was a revelation. Once per week, we learned ten new vocabulary words. I can still remember some of them—can in fact still see her writing them on the board in that old firetrap classroom with the giant, wavy glass window. What words they were! Macabre, limn, complement (not compliment!), vapid, esoteric. Mrs. Marks would write the phonetic spelling, complete with the vowel signs, first, and we would try to pronounce them before we saw the actual spelling. This was one of my favorite activities. I found I was quite good at it, and, to my delight, she thought so too.

The years went by. Mrs. Marks was my English teacher for both the 8th and 9th grades. She took off the 1980-1981 school year to have a child. I was not amused, but I was glad to see her back for my junior year. By then, I was confident, enthusiastic, and a devourer of books. There seemed to be a special level of understanding between us. When she instructed the class to choose a major work for our junior book report, I came to her with John Steinbeck’s East of Eden. I knew of Steinbeck, but I knew nothing about the book, and she seemed concerned. After giving it some thought, she said she was going to let me report on it. East of Eden was “mature,” she said, adding, “I probably would not let any other student do it, but I’ll let you do it.” Flattered, I threw myself into this painful novel, with its tortured psyches; its notorious, fetishistic brothels; and its deeply flawed characters. As I read, and as the story became more troubling, I sensed the trust that Mrs. Marks had reposed in me with this assignment, and the risks she was taking. When the time came to write my report, I dispensed with euphemisms, boldly incorporating the word whorehouse into my text. I felt that I was taking a chance using such an offensive term in a book report for a female teacher (or any teacher), but she trusted me, so I trusted her. She never said a word about it. She treated that daring word as though she had run across it in The New Yorker, rather than in a high school junior’s book report. More than three decades later, I can still recall how it felt to be treated that way—like an adult, maybe even a budding intellectual.

In my senior year, we did more writing, more reading, and more speaking. The latter has served me well. Here, too, I took chances because Mrs. Marks allowed it. For my spoken piece, which I was to annotate for emphasis, breathing, and inflection, I chose the ghastly shooting scene from William Manchester’s The Death of a President:

The Lincoln continues to slow down. Its interior is a place of horror. The last bullet has torn through John Kennedy’s cerebellum, the lower part of his brain. Leaning toward her husband Jacqueline Kennedy has seen a serrated piece of his skull—flesh-colored; not white—detach itself. At first there is no blood. And then, in the very next instant, there is nothing but blood . . .

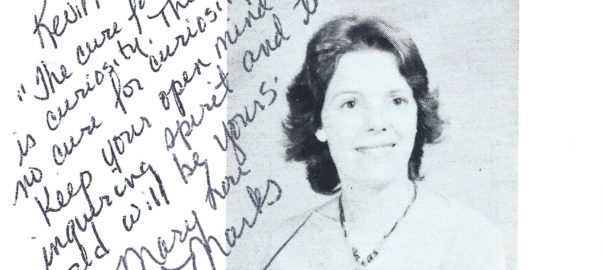

Today, it is easy to imagine a teacher rejecting a request to work with such material. Mrs. Marks knew it mattered to me, so she allowed it. I guess that is why I still remember it so clearly. In retrospect, I can see that her test for such things was good faith. Anything worthwhile that you wanted, in good faith, to do, she encouraged. Accordingly, that spring, she signed my final yearbook:

Kevin-

‘The cure for boredom is curiosity.

There is no cure for curiosity.’

Keep your open mind and

inquiring spirit and the

world will be yours.

Mary Lou Marks

As my final year of high school drew to its close, I knew I was well-prepared for the verbal and literary challenges of college, and I knew it was time for a change. I was ready. I guess Mrs. Marks felt the need for a change too. I was not surprised to learn that my last day as a student at Big Sandy School was to be her last there as a teacher. As I went away to college, she was settling into her new position as the librarian and media specialist at Camden Central High. She has been there ever since, compiling material, transitioning to electronic media, and—unsurprisingly—running writing workshops for the students there.

I never became the great writer, but I write still—nonfiction, mostly—and I did become a teacher. Though not at the same school, Mrs. Marks and I have now been colleagues in the Benton County school system for 22 years. During that time, we have had many opportunities to share ideas, written passages, and social criticism; Facebook has made this easier still. Now, at long last, she has decided to retire. I know what she will do: she will travel, and raise her flowers, and visit museums and art exhibits, and watch her grandchildren grow up. And she will read, and read, and read. Behind her, she will leave several generations of men and women from a pair of small towns who will never forget what she gave to them: eyes and ears attuned to words; the ability to connect the imaginary to the concrete; the capacity to gaze across time and space through a book or a story or a poem and to feel the still-beating hearts of writers long dead.

I hope the people of Benton County know how fortunate they have been to have, in their schools, this cultured, literate teacher, who has given selflessly to them, their children, and probably their grandchildren, for nearly four decades. A few years back, Mrs. Marks commented about my vocabulary and my love of history and words. I replied to her the only way I felt I could. I said simply, “I had a teacher who cared about words and beauty and culture and taught me to do the same.”

I know that in this I am not alone.

Well done, Mrs. Marks.

Well done.