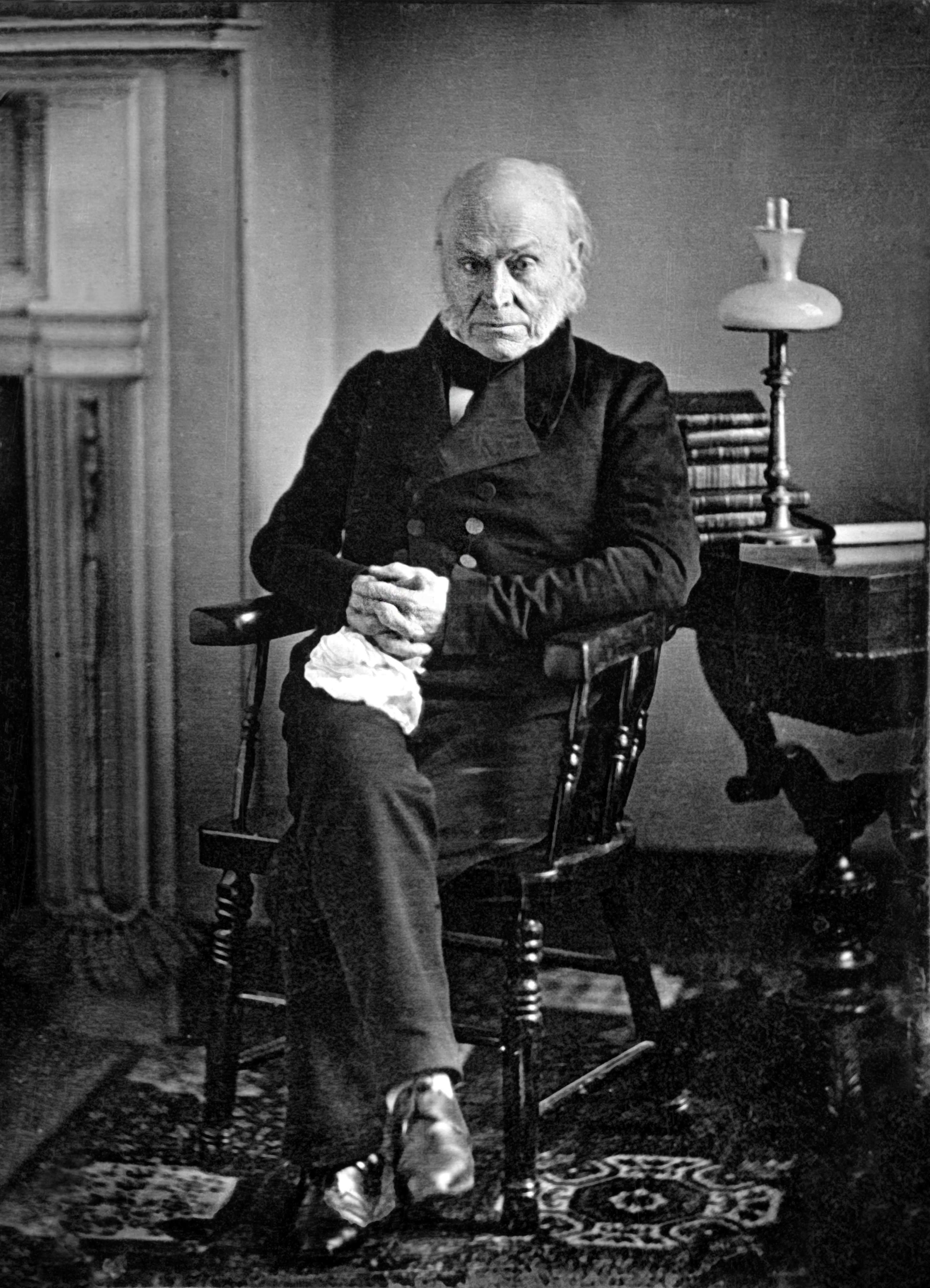

On February 21, 1848, Congressman John Quincy Adams, representative of the Plymouth District of Massachusetts, collapsed from a stroke at his desk in the chamber of the House of Representatives. Adams was 80 years old and had endured a cerebral hemorrhage in 1846, which had left him frail and weakened. Now too ill to be moved farther, the fallen legislator was taken to an office just off the House chamber (now Statuary Hall), where he lingered for two days before dying there on February 23.

For seventeen years, this most unique of congressmen had exploited his combination of notoriety, fame, experience, talent, and unparalleled links to the Founding Fathers to fight against the institution of slavery, an institution that he feared might eventually destroy the Union.[1] For seven of those years, he struggled incessantly against the infamous “Gag Rule,” to restore and defend the right of members of Congress (and, by extension, their constituents) to openly discuss abolition petitions. He fought his final struggles against the annexation of Texas and against the Mexican War, because he saw within those issues more portents of national peril related to—again—slavery.

Adams’s concern with slavery was not new, though it had acquired a new fire and urgency. Beginning during his tenure as secretary of state, he spoke out and acted against the institution and the political and social dangers it threatened in a republican society. Though he often accommodated, tolerated, or even excused slaveholders themselves in his public and private life and sometimes ignored the issue in pursuit of his own political ends, his voluminous diary, one of the greatest ever kept by an American public figure, reveals a man deeply troubled by the “peculiar institution.” Adams was, in short, a foe of slavery who viewed it with personal disgust. Throughout his career, this sentiment grew more profound and colored his public and private relationships, affecting his opinions of and interactions with other public figures.

As the years passed, and as Adams aged, he narrowed his focus. By the time of his death, he had faced slavery down on several fronts. John Quincy Adams, the anti-slavery politician, had become “Old Man Eloquent,” Congressman John Quincy Adams, the abolitionist. In retrospect, his struggles in the House of Representatives, in the 1830s and 1840s, coupled with his many passionate (and accurate) predictions, make Adams the metaphorical link between that period’s naive denial on the slavery issue and the portentous and explosive alarms of the 1850s. “It is altogether fitting and proper,” concluded William Lee Miller, in Arguing About Slavery: The Great Battle in the United States Congress, “for the purposes of the inner history and collective memory of the American people, that on the day that Adams fell there was seated, in a not very good seat in the back row of the House chamber, a young Whig congressman from Illinois serving his first and only term . . . Abraham Lincoln.”[2]

Though perhaps not among the best-known figures in American history, Adams certainly fits neatly into the second tier of better known. This is in large part because of his long and varied career in public service. Some have noted that Adams’s public life, perhaps more than those of some other historical figures, can be neatly divided into phases. The first phase consisted of his early life and career prior to his inauguration as president in 1825. This period included his time in Massachusetts state government, brief membership in the United States Senate, and diplomatic travels throughout Europe, culminating in his service as Secretary of State under President James Monroe. The second phase consisted of his single term as president from 1825 to 1829. Finally, the third phase consisted of Adams’s post-presidential career as a member of the United States House of Representatives, beginning in 1831.[3] This final period was, in many ways, the most storied, for it was from his humble (for a former president) House seat that Adams emerged as a leading abolitionist and brought to the forefront of public debate many of the issues that would, after his death, push the United States toward civil war.

John Quincy Adams was born on July 11, 1767, in what is now Quincy, Massachusetts. It seems that slavery played little part in his early life; there were few slaves in Massachusetts, and the practice would be abolished there in 1781.[4] He was born a subject of King George III of Great Britain, but the relationship between Britain and its American colonies in general, and Massachusetts in particular, was already beginning to unravel. His mother, the literate and determined Abigail Adams, stood faithfully behind his father, John, who was already emerging as a leading figure in New England’s growing impatience with British colonial policy. When John Quincy was nearly nine, his father was a member of the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia and served on the committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence. By then, fighting had already erupted between Americans and the British Army.

With war underway, in 1778, at the age of eleven, John Quincy accompanied his father to Europe, where the elder Adams was to represent American interests in the Netherlands. The following year, the two returned to the United States, only to depart again for Europe three months later. It was on this second voyage that the twelve-year-old John Quincy began to keep a diary at his father’s suggestion.[5] He would continue the journal, with some interruptions, for the rest of his life.[6] Over the next five years, as the War for Independence concluded, John Quincy attended school in Holland and served his father and a number of other diplomats in various posts throughout Europe. In 1785, he returned home to Massachusetts to attend Harvard, from which he graduated in 1787, just as the Framers of the Constitution were meeting in Philadelphia.

In 1790, while his father was serving as vice president of the United States, Adams opened a law office in Boston. He soon began to make public declarations on controversial matters, openly supporting the second term policies of the Washington administration involving neutrality in the European wars and the “Citizen Genet” controversy.[7] Washington was pleased. In 1794, he named Adams Minister to the Netherlands, and Adams again traveled to Europe. While visiting London, in 1795, Adams met and became engaged to American Louisa Catherine Johnson, the daughter of a United States Consul.

In May 1796, President Washington named Adams Minister to Portugal. Several months later, John Adams the elder was elected president of the United States and sent his son to Prussia instead. John Quincy married Miss Johnson before traveling to Berlin, where their first son was born in 1801. That same year, the House of Representatives resolved the disputed election of 1800 by naming Thomas Jefferson president over his own ambitious “running mate,” Aaron Burr, and their Federalist opponent, the senior John Adams. With his father no longer in power, John Quincy and his family returned to Boston.

In 1802, Adams was elected to the Massachusetts State Senate and later ran unsuccessfully for the US House of Representatives. The following year, the Massachusetts legislature elected him to the United States Senate. In 1803, Adams supported President Jefferson’s purchase of the Louisiana Territory, angering all the other Federalist members of the Senate.[8] Over the next few years, he grew increasingly alienated from the foundering Federalists and became more and more aligned with the Republicans. In 1809, President James Madison appointed him to represent the United States in Russia. He was in St. Petersburg, in 1812, when war erupted between the United States and Great Britain. In 1814, President Madison named him to the peace delegation in Belgium, where he helped craft the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812. Madison subsequently named Adams Ambassador to Great Britain.

In 1816, James Monroe was elected president. Three days after his inauguration, Monroe named Adams secretary of state. It was in this position that Adams first began to gain national acclaim. It was also as secretary of state that he first expressed his grave misgivings regarding slavery and the impact of the growing sectional tensions on the Union.

Agitation over the slavery issue was nothing new, reaching far back into the nation’s founding. In 1819, however, it burst upon the national consciousness with an urgency and vitriol never before seen. On February 16, Adams made his first significant diary reference to the divisive political and sectional effects slavery was about to unleash. In the midst of a protracted discussion of his delicate negotiations with Spain over Spanish Florida, Adams related that a new controversy had arisen. “The excessive curiosity upon the subject of this negotiation with Spain,” he wrote, “is qualified only by the agitation of a new question in the House of Representatives, on a bill for admitting the Missouri territory into the Union as a State. A motion for excluding slavery from it has set the two sides of the House, slaveholders and non-slaveholders, into a violent flame against each other.”[9]

The Missouri statehood controversy was to expose the growing sectionalism congealing around slavery. The North clearly dominated the South in population, virtually guaranteeing the former’s ongoing control of the House of Representatives and someday, perhaps, the presidential election process. Only a carefully controlled balance between the raw numbers of slave and free states could prevent the North from seizing control of the Senate as well. In 1819, there were eleven free and eleven slave states. “Slavery is already well established in Missouri as it was part of the original Louisiana Purchase,” Adams told his family. “But to admit the territory as a slave state would upset the sectional balance.”[10] Adams also recognized that there was more at stake than just the Senate majority (or parity, at least) so cherished by the South. Northern politicians knew that the Constitution’s “Three-Fifths” formula for calculating the “representation” of slaves greatly exaggerated the relative voting power of whites in a slave state. With the North dug in against this expansion of pro-slavery voting power and the South coveting additional Senate seats and protesting that slaves were just another form of property, the stage was set for a crisis.[11]

One of Adams’s first keen insights into the Missouri crisis was that anti-slavery forces suffered from a lack of resolve and oratorical talent relative to the southerners, who also, presumably, had more to lose in the struggle. “The slave-holders are much more ably represented than the simple freemen,” [12] he lamented on January 16, 1820, later adding, “Never since human sentiments and human conduct were influenced by human speech was there a theme for eloquence like the free side of this question now before the Congress of this union. By what fatality does it happen that all the most eloquent orators of the body are on its slavish side? There is a great mass of cool judgment and plain sense on the side of freedom and humanity, but the ardent spirits and passions are on the side of oppression”[13]

Not all of the great orators were on Congress’s “slavish side.” One member of Congress whom Adams believed could hold his own against the pro-slavery forces was Senator Rufus King of Massachusetts. On February 11, 1820, Adams attended Senate debates and heard King speak on the Missouri issue. “There is nothing new in his argument,” Adams wrote later, “but he unraveled with ingenious and subtle analysis many of the sophistical tissues of the slave-holders. He laid down the position of the natural liberty of man, and its incompatibility with slavery in any shape.”[14] The slaveholders present, Adams reported, “gnawed their lips and clenched their fists as they heard him.”[15]

Attending a dinner party that night at the home of Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, Adams found little discussed besides Senator King’s speech. The Secretary of State had always opposed slavery. He loved, admired, and sought to emulate his aged father. The elder Adams was, thus far, the only American president who had never owned slaves and had once denounced “Negro slavery” as a “foul contagion in the human character.”[16] Still, like his father, John Quincy had always been tolerant of, and at times even admiring of, some slave-holding leaders. For the younger Adams, these included his dinner host, Calhoun; House Speaker Henry Clay; and Adams’s own employer, President James Monroe.

Now, with the Missouri crisis underway, Adams’s opinions—his private opinions, at least—began to undergo a transformation. His growing sense of a threat to the Union, his realization that the antislavery forces were rhetorically outgunned, and his growing admiration for Senator King and his controversial speeches, brought out in Adams a fire that had been lacking on the question of the South’s “peculiar institution.” Writing of Calhoun’s party in his diary, Adams bitterly denounced “slave-holders” as unable to bear King’s speeches “without being seized with cramps.”[17] Expanding on his earlier theme of the want of spokesmen for the antislavery cause, he branded slavery “an outrage upon the goodness of God,” to someday be laid “bare in all its nakedness.”[18] The man who could do this, Adams concluded, “would perform the duties of an angel upon earth!”[19]

In the end, the Missouri question was, as Adams had believed it would be, settled by a compromise. Congress admitted Missouri to the Union as a slave state. The fortuitous statehood application of slave-free Maine (originally part of Massachusetts) smoothed over the issue of Senate balance. While it was, perhaps, galling to have a new slave state enshrined so far north and west, and so close to the Old Northwest, from which the Confederation Congress had long ago barred slavery, Adams was not altogether disappointed. Where slavery already existed within the Louisiana Territory (such as in Missouri, and now Arkansas), he considered it “impracticable” to attempt to admit those areas to statehood with slavery forbidden or restricted.[20] He continued to believe, however, that Congress could ban slavery from territories where it did not exist (Adams referred to those who did not believe this as “zealots”) [21] and could set freedom as a condition of statehood in such places.[22] The “Missouri Compromise,” as it came to be known, mirrored this belief by forbidding slavery in the Louisiana Purchase north of Missouri’s southern boundary, with the exception of Missouri itself. Adams considered this last principle, the power of Congress to prohibit “the introduction of slaves into future Territories,” as “a great and important point secured.”[23]

Disaster had been averted; disunion had not come. Across the country, though, thoughtful men, many known personally to Adams, had expressed new and alarming visions. Thomas Jefferson, retired to Monticello in his late seventies, called the crisis a “fire bell in the night,”[24] and famously likened the existence of American slavery to “holding a wolf by the ear.”[25] Henry Clay, who would ultimately help create the compromise legislation, had told Adams with certainty “that within five years from this time the Union would be divided into three distinct confederacies.”[26] Secretary of War Calhoun, a southerner whom Adams greatly admired, said that if “disunion” should come, “the South would be from necessity compelled to form an alliance, offensive and defensive, with Great Britain.”[27] When Adams suggested that the North would thus be left with no choice but to force its right to “move southward by land,” Calhoun alarmingly speculated that, in such an event, the South would be forced “to make [its] communities all military.”[28]

Adams did not pursue this troubling conversation with Calhoun, but later reflected on it at great length, concluding that disunion caused by slavery would inevitably result in “universal emancipation.”[29] He reasoned that it might even result in the eventual disappearance of the African race in America.[30] He concluded that such disunion would likely prove temporary, and that if the nation could then be restored, free of the “great and foul stain” of slavery, the ordeal would be worth the price.[31]

All of this was, of course, philosophical speculation about something that had seemingly been avoided. It is an earlier observation, at the beginning of the Missouri Crisis, which today stands as Adams’s most famous and poignant forecast. “I take it for granted,” he confided to his diary on January 10, 1820, “that the present question is a mere preamble—a title-page to a great tragic volume. . . . [President Monroe] thinks this question will be winked away by a compromise. But so do not I. Much am I mistaken if it is not destined to survive his political and individual life and mine.”[32]

In the years after the passage of the Missouri Compromise, the United States settled into a false optimism on the slavery question. In the autumn of 1820, Monroe was reelected president, and Adams remained as Secretary of State. He accepted the reality of the Compromise, while continuing to bristle at the notion of slavery in Missouri. Meanwhile, he oversaw a long-needed reorganization of the Department of State. The office was in some disarray when Adams arrived, in 1817. Papers were often lost, and the filing system was nearly nonexistent. Still, he could say little; President Monroe was his predecessor at the post.[33] As he brought order to the department, he kept up diplomatic correspondence, advised the president, and wrote in his diary. He also considered whether he might like to follow Monroe into the White House.

The presidential election of 1824 was one of the most divisive in American history, which is ironic, given that political parties, as they had been previously understood, had all but ceased to exist. What resulted, rather than the relative harmony that had reigned under Monroe, was emerging sectionalism and personal animosity. The electoral votes were divided among four men. Andrew Jackson had the most. Adams was in second place, with Treasury Secretary William Crawford and Henry Clay in third and fourth, respectively. None of the four had the necessary majority for election to the presidency.

Under the Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution, the names of the top three electoral vote winners were to be submitted to the House of Representatives. There, voting by states, each state having only one vote, the representatives were to choose the president, a majority of the states being necessary for election. With the fourth-highest number of votes, Clay was out of the House contest. At this crucial point, Crawford suffered a stroke and became too ill to run or serve. For reasons that are still not altogether clear, Clay’s supporters decided to cast their states’ votes for Adams, choosing him as the sixth president of the United States and the second (and last) chosen by the House of Representatives. Secretary of War Calhoun received a majority of the electoral votes for vice president in the original balloting, making a Senate choice for that post unnecessary. Adams later appointed Clay secretary of state, giving rise to the infamous charge of “corrupt bargain,” which was bandied about by Jackson’s supporters and has followed Adams throughout history.

As president, Adams proposed an ambitious program of “internal improvements” including roads, bridges, canals, a national university, better schools, and a national observatory. These lofty goals were widely ridiculed by his enemies, of which there were more than enough to kill the proposals, especially after the Democratic victories in the midterm elections of 1826. In retrospect, much of the criticism of the president’s program was rooted in anti-intellectualism and its complex relationship to political power. “Few politicians wanted an enlightened populace,” wrote Mary Hoehling. “The untutored were easily swayed. Newspapers across the land lampooned Adams’s ‘lighthouses in the skies,’ as he had unfortunately called observatories, and painted a lurid picture of the proposed national university where unsuspecting youth would surely be imbued with dangerous ideas.”[34]

Beyond simple ridicule, Adams’s opponents attacked his programs on the ground that they lacked constitutional authorization. Thus, the old argument of Strict Constructionism, which had so troubled Jefferson, became the primary tool used by southerners and others to deny Adams legislative successes. In Arguing About Slavery, however, William Lee Miller suggested that Adams’s opponents had hidden agendas that went beyond mere constitutional philosophy. “The latent issue of slavery,” he wrote, “ran silently—usually silently—underneath almost everything.”[35] For Miller, it was their concern that Adams was not “sound” on the slavery issue that governed the southerners’ response to seemingly unrelated facets of his presidential programs.[36] Adams was too soft on the Indians. What if this softness “might apply to blacks as well”?[37] “The ‘National’ program that he proposed,” Miller said, “would have enlarged federal powers in a way that might one day threaten slavery. The ‘strict construction’ of the Constitution and states’ rights that his opponents insisted upon were . . . barriers of protection against interference with slavery. Both sides felt that his energetic program of federally aided ‘improvement’—commercial, intellectual, industrial, scientific, moral—implied a culture at odds with the culture of a slave society.”[38] Had he read it, Adams might have seen Miller’s latter analysis as the ultimate endorsement of the wisdom of his programs. His moral self-assurance, however, could not pass his ideas into law. President Adams saw few successes, and came to see little prospect of any, telling the Cabinet, “The lines of the political combination against us is clear.”[39]

Those lines appeared early when, for the only significant time in his presidency, the “latent issue of slavery” did not run “silently underneath,” but boiled to the surface.[40] In December 1825, Adams named American delegates to the Panama Congress, a meeting of representatives of the newly liberated nations of Latin America. According to John T. Morse, Jr., an early Adams biographer, it had become customary for presidents to personally decide whether the United States should participate in new missions and then simply appoint the representatives without consulting Congress. If Congress found some fault with the mission, the Senate could simply refuse to approve the nominations. This time, however, things did not go according to custom. The Congress, predisposed against Adams, accused him of exceeding his powers.[41]

The objections to participation in the Panama Conference came from the South, and, in reality, had little to do with Adams overstepping his authority. It was the Conference’s links—real and imagined—to slavery that raised the ire of members of Congress. The Latin American countries in question had freed their slaves. This obviously did not sit well with some slave-holding Americans. More important was the possibility that Haiti, a state that owed its existence to the greatest fear of the American South—servile insurrection—might be represented at the Conference. “The South . . . hated this Panama Congress with a contemptuous loathing,” wrote Morse.[42] “That the president of the United States should propose to send white citizens of that country to sit cheek by jowl on terms of official equality with the revolted blacks of Hayti fired the Southern heart with rage inexpressible.”[43] “Southern leaders exploded,” added Miller, writing nearly a century after Morse, to think that the president would send Americans to “a conference that might well discuss such forbidden topics as slavery and the slave trade, and—worse—relations with the newly independent black nation of ‘Hayti.’”[44] In the end, Adams sent his delegation, but the affair was a disaster. The commissions were so long delayed that Americans played no significant role at the meetings.[45]

The Panama debacle came early in Adams’s administration, but it set the tone for three more years of frustration. By the end of his term, Adams had endured scathing attacks at the hands of the Democrats and their supporters. The Jacksonians had vowed to unseat him, and though Adams had little doubt that they would do so, he determined to enter the coming presidential race.[46] The election of 1828, one of the most personal and hate-filled political campaigns in the history of the Western World, brought John Quincy Adams’s presidency to a merciful end. Driven from office by Andrew Jackson, a slaveholder who enjoyed personal appeal far beyond his class and region, Adams likely considered the parallels to his father’s defeat by Jefferson in 1801. Certainly, he followed his father’s example in foregoing the tradition of attending his successor’s inauguration. Unlike his father, however, he did not leave Washington immediately, but remained until July.

Adams was both bored and bitter. After leaving the White House, he wrote, “The greatest change in my condition occurred at the beginning of this month which has ever befallen me—dismission from the public service and retirement to private life. After fourteen years of incessant and unremitted employment, I have passed to a life of total leisure; and from living in a constant crowd, to a life of almost total solitude.”[47] In the months before he returned to Quincy, he read, corresponded, and (in a way impossible to comprehend today) regularly rode his horse about Washington, sometimes stopping to converse with other riders, even members of Jackson’s administration. On July 8, Adams had such an encounter with Secretary of State Martin Van Buren, exchanging dubious pleasantries with the New Yorker, whom he secretly (and correctly) regarded as “the manager by whom the present Administration has been brought into power.”[48] Adams later characteristically predicted that Van Buren would eventually be betrayed, and that such “a reward of treachery” would “be but his desert.”[49] Though commenting earlier that Van Buren had been the only member of the new administration to show him the “mark of common civility,”[50] Adams coolly dismissed the others. “I never was indebted for a cup of cold water to any one of them,” he wrote, “nor have I ever given to any one of them the slightest cause of offence.”[51] He caustically concluded, “‘odisse quem læseris:’ they hate the man they have wronged.”[52]

Shortly after his impromptu encounter with Van Buren, Adams returned home to Quincy. There, he began the task that he thought would occupy the rest of his life: the cataloging and organization of his father’s papers.[53] Months earlier, even before leaving the White House, in the dismal autumn of 1828, a friend had asked him if he would consider foregoing complete retirement in favor of a Massachusetts seat in the United States Senate. Adams temporized, saying that he did not wish to “displace any other man,” and that he intended, “to go into the deepest retirement, and withdraw from all connection with public affairs.”[54] Two days later, however, Adams told another friend that in retirement he would follow the principle that he had always followed, seeking no office, but rising to accept “any station that they may assign to me.”[55]

Little more was said about the prospect of a Senate seat. In Quincy, meanwhile, things did not go well. The entire Adams family was in deep mourning. In May, the Adamses’ son, George, a ne’er-do-well attorney who had been a continual source of embarrassment and concern, died, either through suicide or through accident, aboard a steamship. Believing that her husband’s relentless ambition for his sons had helped ruin George, Louisa Adams bristled at any mention of further public office. [56] Both she and her remaining sons bristled when talk turned from the Senate to the House of Representatives.[57]

In 1830, Boston area National Republicans told Adams that unless he agreed to run for the Plymouth district’s House seat, which was soon to be vacated, it would likely be lost. Adams said that he would accept the seat only if he were chosen by a large margin. To his delight, on November 1, 1830, he was easily elected. Eventually, Louisa accepted the fact that she was again to move to “a house which will become the focus of intrigue,” and the Adamses prepared to return to Washington.[58] In December 1831, Former President John Quincy Adams took his seat (seat 203) in the United States House of Representatives. Contrary to his son, Charles, who thought it a disgrace for a former president to accept a seat in the lower house of the legislature,[59] Adams had written that he had “no scruple whatever” on the subject, adding, “No person could be degraded by serving the people as a Representative in Congress. Nor, in my opinion, would an ex-president of the United States be degraded by serving as a Selectman of his town, if elected thereto by the people.”[60]

For several years after the commencement of his service in the House of Representatives, Adams said little about slavery and rarely became involved in the topic. Like many northern congressmen, he routinely received petitions from abolitionists or antislavery groups. Some of these called for the congressional abolition of slavery everywhere, a proposition regarded by nearly everyone as not only impossible but manifestly unconstitutional. Others called for the abolition by Congress of slavery in the District of Columbia, a much more realistic, and consequently much more troublesome, proposition.

At regularly scheduled sessions set aside for the purpose, Adams, like others, dutifully presented to the House the petitions from his constituents. He also presented petitions from others, all over the country. There was a silent understanding within the House that the antislavery petitions would come to nothing, and like many other presenters, Adams acknowledged that he submitted them as a duty to the people and not because he necessarily supported their objectives. Normally, such petitions were sent to committee, where they quietly died, while even a foe of slavery such as Adams could console himself that to pursue them would be fruitless and destructive.[61]

In the winter of 1836, however, John Quincy Adams’s role in the House of Representatives and in the history of slavery in the United States began to change. Southern members had grown increasingly impatient with the anti-slavery petitions, which had increased in number and in stridency. Desiring to quiet the slavery question in preparation for the 1836 presidential election, and presumably for all time to come, the House created a select committee, the Pinckney Committee, after its chairman, South Carolina’s Henry L. Pinckney, to work out a way of disposing of all present and future antislavery petitions simultaneously. As expected, the committee reported that the Congress did not have the constitutional authority to interfere with slavery in the states and that Congress should not interfere with slavery in the nation’s capital. This much had been expected. Finally, however, the committee report added a provision calling for the automatic tabling of all motions and petitions relating to slavery. Thus, in the future, there could be no debate and no discussion of any kind on the topic of slavery. Members would be procedurally forbidden to speak of the matter. Materials relating to slavery could not even be printed. [62] As Congress prepared to vote on the committee report, Adams rose to speak, but his colleagues used parliamentary rules to quiet him.

In the course of the vote on the various provisions of the Pinckney Committee report, Adams dropped a rhetorical bomb on the House of Representatives. The old man rose and suggested that the one thing on which all present thought they agreed—that Congress had no authority to interfere with slavery in the states—was not necessarily true after all. He painted a horrifying picture in which the South’s insatiable appetite for the expansion of slavery would eventually lead to wars of all types: with foreign countries, with Indians, and with the slaves themselves. Would not the South call upon the Congress and the North for assistance, he asked. Would not the rendering of that assistance and the possible subsequent use of the treaty powers of the United States constitute “interference with slavery”?[63] Many members recoiled from this notion that, years later, would form part of the justification for the Emancipation Proclamation.[64] On May 26, 1836, the provisions of the Pinckney Committee report, including the provision calling for the automatic tabling of slavery motions, overwhelmingly passed the House of Representatives. When the Speaker called upon him to vote, Adams said, “I hold the resolution to be a direct violation of the constitution of the United States, the rules of this House, and the rights of my constituents.”[65]

The battle against the Gag Rule had begun.

It seemed, at first, that the Gag Rule might be simply a transient procedural nuisance. The lame duck congressional session of December 1836 brought a significant, albeit brief victory for Adams. When called upon to present petitions, Adams introduced one calling for abolition generally and for abolition in the District of Columbia, specifically. When a member from South Carolina attempted to intervene, invoking the Gag Rule, The Speaker of the House, James K. Polk of Tennessee, a slaveholder and a future president, ruled him out of order. Polk determined that the Gag Rule had expired with the earlier session. Adams wrote almost nothing about this fortunate event, perhaps sensing that it would be short-lived. Some members were convinced that the gag had become indispensable and had come to describe, it in florid, almost religious, language, as the salvation of the Union from the abolitionists. Pinckney of South Carolina, the author of the original Gag Rule, declared, regarding the need to suppress the abolitionist petitions, “But repress agitation—give no scope for turmoil—nail the memorials to the table—allow no discussion or action on them—and having nothing to go on, no flame to fan, no strife to stir, it must necessarily droop and die, and soon cease to infect us with its pestiferous breath.”[66] Albert Hawes of Kentucky reintroduced the original text of the Pinckney Gag Rule, and it easily passed the chamber.

Determined, now, to fight it out in the open, in February 1837, Adams embarked upon one of the most colorful episodes of his life. Unfortunately, the period corresponds with a hiatus in his journal, extending to April, so we have none of his personal reflections on the matter. It was during this time that Adams began to introduce petitions from blacks, often employing subtlety, deception, and sarcasm, and sometimes infuriating southern members, leaving them not quite certain whether or not he was being subtle, deceptive or sarcastic. The southerners were insulted, and the result was a parliamentary uproar. When Adams proposed to send to the speaker a petition alleged to be from actual slaves, Representative Dixon Lewis of Alabama moved to punish him, suggesting that if the Massachusetts representative were not upbraided for this outrage, the southern members should leave the House and return to their states. Julius Alford of Georgia punctuated this alarming motion by proposing that the petition be physically removed from the House and burned.[67]

On February 9, Representative Waddy Thompson of South Carolina moved to censure Adams and to escort him to the front of the House for official denunciation. Rising to defend himself, Adams revealed—he had not been given time to present the content of the resolution and, in fact, had not attempted to do so—that the petition was actually from slaves calling for his (Adams’s) expulsion from the House of Representatives! Humiliated, and realizing they had been tricked, furious southerners stepped up their punishment efforts. Over the next few days, Adams’s opponents made blistering speeches, expressing about slaves sentiments that were considered extreme even by the standards of the 1830s. Pinckney of South Carolina declared that he “would just as soon have supposed that the gentleman from Massachusetts would have offered a memorial from a cow or a horse—for he might as well be the organ of one species of property as another. Slaves [are] property,” he emphatically declared.[68] In the end, the House did not censure Adams, but it did vote to reject his petition on the ground that it violated the “dignity” of the House and the “rights” of slaveholders.[69] On February 12, the House, by a huge margin, declared, “that slaves do not possess the right of petition secured to the people of the United States by the constitution.”[70]

Every year, every term, every session, Adams attempted to present slavery motions. At the beginning of each term, he moved to rescind the Gag Rule, which by this time was a genuine rule, rather than a simple resolution that required passage each term. In the meantime, his abolitionist tendencies grew and he became involved in outside projects, one of which became a cause célèbre.

In 1839, near Cuba, thirty-nine Africans on an illegal Spanish slave ship, the Amistad, rebelled, killed two crewmen, and demanded that they be returned home.[71] The crew instead took them to New York, where they were captured and held as prisoners in Connecticut. The Africans were subjected to intense press scrutiny and humiliating cruelty. Abolitionists adopted the cause as their own, filing suit in federal court for the release of the men and embroiling the United States in an international incident with Spain. The abolitionists expected little from Judge Andrew Judson, who was a well-known white supremacist, but were surprised when he ruled in favor of the prisoners and instructed the government to return them to their homes. The Van Buren administration appealed the case to the Supreme Court. The abolitionist leader Lewis Tappan appealed to Adams for help, not because he was a great lawyer—he was long out of practice—but because he would draw publicity to their cause.

Adams reluctantly accepted Tappan’s call to assist counsel in the Amistad Affair, as it came to be known. Though not the lead attorney, he agonized over the case, considering himself wholly unprepared for the challenge. “I walked to the Capitol with a thoroughly bewildered mind,” he wrote during the preparation of the case, “—so bewildered as to leave me nothing but fervent prayer that presence of mind may not utterly fail me at the trial I am about to go through.”[72] Adams’s confidence returned as he argued before the Supreme Court. He spoke for more than eight hours over two days and “easily won the case.”[73] The Court ruled that the Africans had been “kidnapped,” and that they did not have to return to Africa but were simply to be released.[74] Adams was pleased, but, once again, the pro-slavery press pilloried him. “Is your pride of abolition oratory not yet glutted?” ran one denunciation. “Are you to spend the remainder of your days endeavoring to produce a civil and servile war? Do you, like Aaron Burr wish to ruin your country because you failed in your election to the Presidency? May the lightning of heaven blast you, and may the great Eternal God in his wrath curse you at the last day and direct you to depart from his presence to the lowest regions of Hell!”[75] Old age was not to afford Adams protection from his enemies.

The year after the Amistad affair brought Adams’s moment of greatest acclaim in Congress when, in 1842, the House tried, more earnestly this time, to censure him and remove him from his new post as the chairman of the House Foreign Relations Committee. Adams, himself, presented a petition, alleged to be from citizens of Georgia, calling on the House to remove him as chairman. He had used this ploy before. Though the Gag Rule prevented him from introducing slavery petitions, if personally charged, the rules required that he be given the floor to defend himself. Chaos broke out in the chamber. Eventually, the southern members surrounded him, calling him names and shouting denunciations.[76] Adams then introduced a petition from some citizens of Massachusetts, calling for the dissolution of the Union on the theory that the South and its backward institutions were costing the North money. At that point, several members introduced resolutions of censure. This move gave him definite right to the floor, which he then used to point out that threats of dissolution of the Union had been southern stock-in-trade for years. Most notably, Adams launched into uncharacteristic personal attacks on members who had long tormented him. Eventually the censure movement died out, as southerners, eager to shut the old man’s mouth, cooled their tempers. Adams emerged from this episode as a hero among antislavery forces, but the Gag Rule remained in place.

When the Twenty-eighth Congress convened for its first session, in December 1843, Adams was there, now 75 years old. He promptly introduced his traditional resolution to eliminate the Gag Rule. The resolution failed, but by a much closer margin than ever before.[77] A little over a year later, after the presidential election of 1844, the same Congress met for its short lame duck session. On December 2, Adams informed the House leadership that the following day he would move to rescind the Gag Rule.[78] The next day, December 3, 1844, Adams introduced the following motion: “Resolved, That the twenty-fifth standing rule for conducting business in this House, in the following words, ‘No petition, memorial, resolution, or other paper praying the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia or any State or Territory, or the slave-trade between the States or Territories in which it now exists, shall be received by this House, or entertained in any way whatever,’ be, and the same is hereby, rescinded.”[79] A Mississippian immediately moved to table the motion, but the motion to table failed by twenty-three votes. The House then voted on the motion to rescind, and it passed by twenty-eight votes.[80] Horace Greely’s New York Tribune editorialized, “Let every lover of freedom rejoice! . . . The Sage of Quincy has won a proud victory for the Rights of Humanity. May he long live to rejoice over it! Here is a motion that will not go backward. There will be no more Gag-Rules.”[81] Adams did rejoice. “Blessed,” he wrote in his journal, “forever blessed, be the name of God!”[82]

“As sometimes happens in life,” wrote Miller, “the door that had been slammed shut repeatedly, and stuck shut and implacably resistant for so long—suddenly swung open.”[83] Historians have identified several reasons why Adams was suddenly able to secure the repeal of the Gag Rule by a comfortable margin. Many of the original supporters of the gag had moved on to other public service or into private life.[84] A companion explanation is that, in December 1844, the Northern Democrats were angry with Southern Democrats for modifying nomination requirements at the party’s presidential convention the previous spring in a way that resulted in the slaveholder Polk wresting the nomination from the Northern favorite, former President Van Buren.[85] Perhaps, on the other hand, years of listening to Adams had changed some minds.[86]

His greatest battle won, Adams now entered a steady decline yet fought on. He had struggled against the annexation of Texas since it had originally become an issue, with Mexican independence in the 1820s and the Texas “Revolution” in the 1830s. Events forced the Jackson administration to abandon its efforts to annex Texas, though Jackson did recognize Texan independence in 1837. The Van Buren administration that took over a few days later had no taste for the fight and left Texas to cultivate relations with Great Britain. Adams sensed that the Texas question would not rest forever.

Adams’s fight against the Gag Rule had taken place against a backdrop of political tumult. In 1840, due primarily to the fallout of the economic Panic of 1837, The Whig Party, with which Adams was loosely affiliated, finally won the presidency and majorities in Congress. The sounds of Whig celebrations had scarcely died away, however, when an unprecedented disaster befell the party. On April 4, 1841, the new Whig president, William Henry Harrison, died on the thirty-second day of his administration, leaving John Tyler, essentially a Southern Democrat—and a very foolish vice presidential choice—in the White House. Adams was appalled when Tyler negotiated a treaty annexing Texas and thrilled when the Senate rejected the treaty. The determined president, however, sought a simple joint resolution of annexation instead. Unlike a treaty, a joint resolution involved the House as well as the Senate, but there was little Adams could do. Both houses passed the resolution, and on March 1, 1845, three days before leaving office, John Tyler signed Texas into the Union. Adams was despondent, calling the annexation “the heaviest calamity that ever befell myself and my country. . . .”[87]

When, in 1846, the annexation of Texas brought war with Mexico, as Adams had always assumed that it would, he stood against the conflict and held in contempt those representatives whom he knew to be against the war but were too afraid others would label them “unpatriotic” to speak against it.[88] The war brought controversy at every turn. Adams became involved in a struggle over the Wilmot Proviso, a bill that Northerners repeatedly introduced in Congress during the period, calling for the prohibition of slavery in any lands the United States might win from Mexico. This proposal was coincident with the widespread realization that the war was sure to greatly increase the size of the United States and bring the slavery controversy to a crescendo.

In November 1846, Adams suffered a cerebral hemorrhage while in Boston. He was confined to bed, or at least indoors, until early 1847, but by February he was back in Washington, where he entered the House chamber to polite applause. He was too weak and tired to take an active role in the many issues swirling around the war. The Wilmot Proviso finally passed the House, with Adams’s quiet support, but failed in the Senate. Unable to speak in a voice that the other representatives could hear, he voted, worked on a single minor committee, and wrote, confident, now, that no great blow would be struck against slavery in his lifetime.

On February 21, 1848, Adams was quietly working at his desk in the House chamber. The business before the House was a motion to award medals to various military officers for heroic conduct the previous year. When the speaker called his name, Adams, bitter opponent of the war to the end, responded with a loud “no.” A few minutes later, he collapsed. Today, in Statuary Hall, the old House chamber, a bronze marker indicates the place where he fell. On February 23, the irritable old man who had served his country in many capacities abroad; had advised presidents; and had, himself, served four years as chief executive, died a few yards away from the site of his greatest glory, seat 203 of the lower house. He had gone there to represent a few tens of thousands of Massachusetts Yankees, yet somehow had emerged as the voice of millions.

John Quincy Adams was always an opponent of slavery. After 1819, however, he came to see it as an abomination against God and the principles of his country’s founding—and he had known most of its founders. After a failed presidency, he found himself in the House of Representatives, a forum in which he could air his increasing frustrations with the South’s oppressive institution and confront its most ardent defenders face to face. There, he threw himself headlong into the battle, tirelessly, and at great physical cost, peeling back and exposing the hypocrisy and self-deception of the planters. He also wove dark and increasingly accurate prophesies of the coming cataclysm he believed awaited his country if it did not abolish and repudiate slavery.

John Quincy Adams once wrote, “A life devoted to [the abolition of slavery] would be nobly spent or sacrificed.”[89] Though it cost him friends, and broke his health, Adams simply seems to have decided that someone with political credentials and a good name—someone with something to lose—had to stand up in righteous indignation and denounce slavery for what it was. Seat 203 of the old House chamber became the pulpit from which he pronounced the judgments of God upon a slave society and upon the free society that tolerated it. It was at work there that he fell. If he did not die in the pulpit itself, he died in the church and in the presence of the congregation.

[1] Charles Francis Adams, ed., Memoirs of John Quincy Adams: Comprising Portions of his Diary from 1795 to 1848 (New York: AMS Press, 1970), 4:502 –03,

[2] William Lee Miller, Arguing About Slavery: The Great Battle in the United States Congress (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996), 514.

[3] The chronology and periodization employed in this work is adapted from Lynn. H. Parsons, ed., John Quincy Adams: A Bibliography (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1993), 1 –9.

[4] Courts ended slavery in Massachusetts. Vermont was admitted as a state four years earlier with a constitutional prohibition against it. See Miller, Arguing About Slavery, 17n.

[6] Ibid. The diary’s maintenance was sporadic until about 1795 when Adams began the earnest effort for which he is well known today.

[7] Parsons, John Quincy Adams, 2.

[10] Mary Hoehling, Yankee in the White House: John Quincy Adams (New York: Julian Messner, Inc., 1963), 127.

[16] Daniel P. Jordan, “Statement on the TJMF Research Committee Report on Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings” at http://www.monticello.org/plantation/hemingscontro/jefferson-hemings_report.pdf, accessed 17 April 2006.

[24] “But this momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror.” Jefferson to John Holmes, April 22, 1820. From Paul Leicester, ed., The Works of Thomas Jefferson, volume 12 (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1905), 158 at http://www.monticello.org/library/reference/famquote.html. Accessed 17 April 2006.

[25] “But as it is, we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.” Jefferson to John Holmes, April 22, 1820, from Paul Leicester, ed., The Works of Thomas Jefferson, volume 12 (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1905), 159 at http://www.monticello.org/library/reference/famquote.html, accessed 17 April 2006.

[26] Adams, Memoirs, 4:525 –26.

[28] Adams, Memoirs, 4:530 –31.

[33] Hoehling, Yankee in the White House, 119.

[34] Hoehling, Yankee in the White House, 144.

[35] Miller, Arguing About Slavery, 175.

[39] Hoehling, Yankee in the White House, 145.

[40] Miller, Arguing About Slavery, 175.

[41] John T. Morse, Jr., John Quincy Adams (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1898), 189 –190.

[44] Miller, Arguing About Slavery, 175.

[45] Hoehling, Yankee in the White House, 144.

[53] Leonard Falkner, The President Who Wouldn’t Retire (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1967), 19.

[54] Adams, Memoirs, 8:80 –81.

[56] Leonard J. Richards, The Life and Times of Congressman John Quincy Adams (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 17-20.

[60] Adams, Memoirs, 8:239 –40.

[61] Miller, Arguing About Slavery, 197 –99.

[71] The details of the Amistad affair are adapted from Richards, Life and Times, 135 –39.

[73] Richards, Life and Times, 137.

[77] Miller, Arguing About Slavery, 481.

[80] Miller, Arguing About Slavery, 482.

[81] Miller, Arguing About Slavery, 477.

[83] Miller, Arguing About Slavery, 476.

[87] Adams, Memoirs, 12:173; Richards, Life and Times, 182.

This was great Kevin. Can’t wait to see more

Thanks!

I was going to leave Alexander Graham Bell’s famous first words to Watson as a test, but it appears the comments are working.

This holds up on second (or fourth) read. Informative and compelling. 🙂

Thanks! I had no idea you had left this. I should have gotten a forward to my phone. Tech details.

This is a great read, and I look forward to future content.

Thanks! I’m glad you enjoyed it!

This is a great read, and look forward to future content.